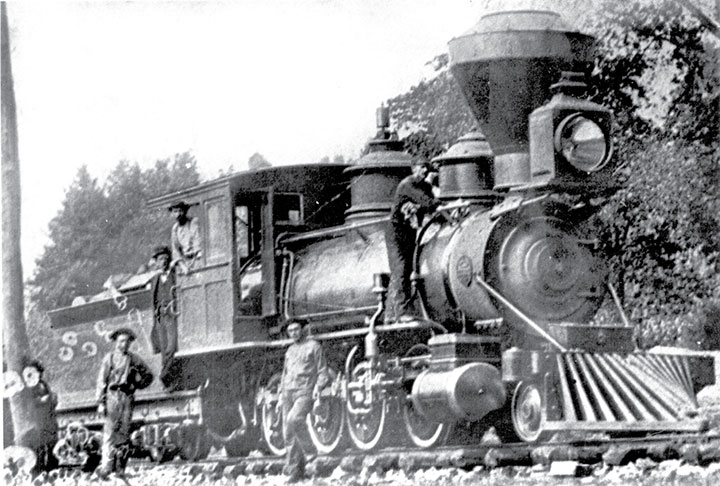

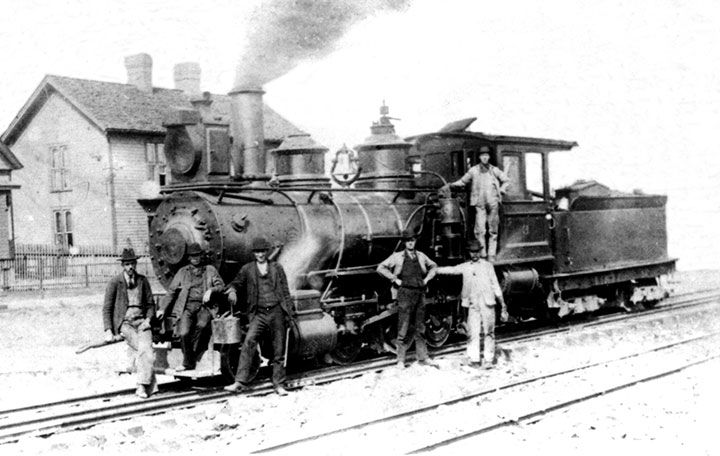

Narrow gauge railroads in the 19th Century tended to promote their passenger service above everything else. Brightly varnished passenger cars and shiny locomotives caught the public eye, luring people to ride the trains for fun, excitement, scenery, and for travel. The passenger trains dominated the timetables, but it was the lowly freight trains that made the money necessary for the company to make a profit. The East Tennessee & Western North Carolina was no exception. While the Moguls I described in the September/October issue caught the eye of the camera, it was ET&WNC’s first Consolidation, #3 (UNAKA) that handled the freight trains through the Doe River Gorge to Cranberry.

The narrow gauge ET&WNC was completed from Johnson City, Tennessee, to Cranberry, North Carolina, and opened on July 3, 1882. Two locomotives had been enough for the construction of the railroad, but once it opened it was clear that more motive power was required. The management went back to the Baldwin Locomotive Works and purchased an off the shelf copy of the fabled Class 60 locomotives used on the Denver & Rio Grande. ET&WNC #3 was built from the same erection drawings as the D&RG locomotives, but differed in only small details, mostly around the cab.

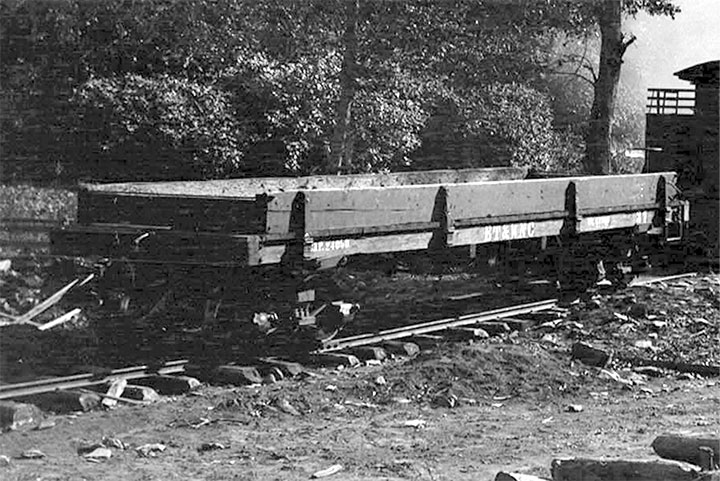

Shortly after the railroad was completed, the company purchased a small fleet of freight cars from the Billmeyer & Small Company of Pennsylvania. Included in the order were ten, 12-ton, 28-foot-long boxcars, and 64 platform cars (flatcars and gondolas) of the same dimensions. From the photos I have seen, all the platform cars had a 15-inch high side and end boards. These cars were used primarily to haul iron ore and other heavy materials.

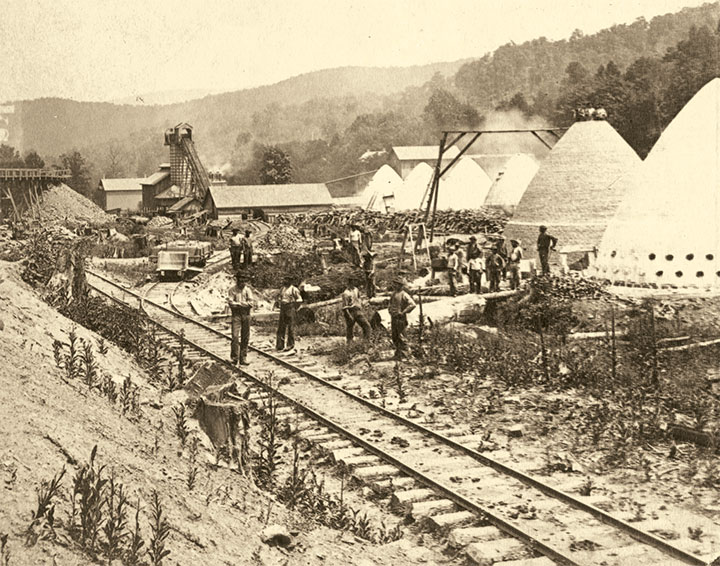

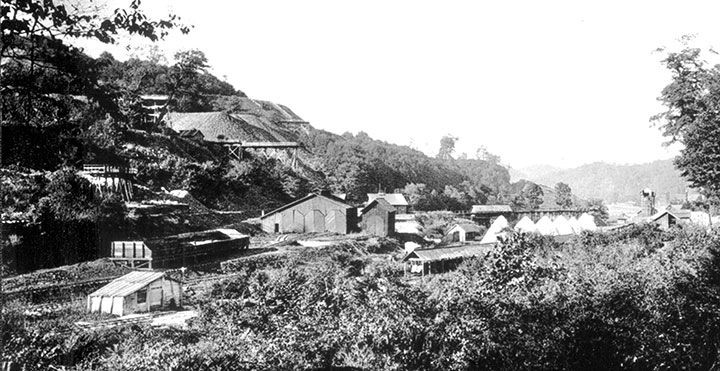

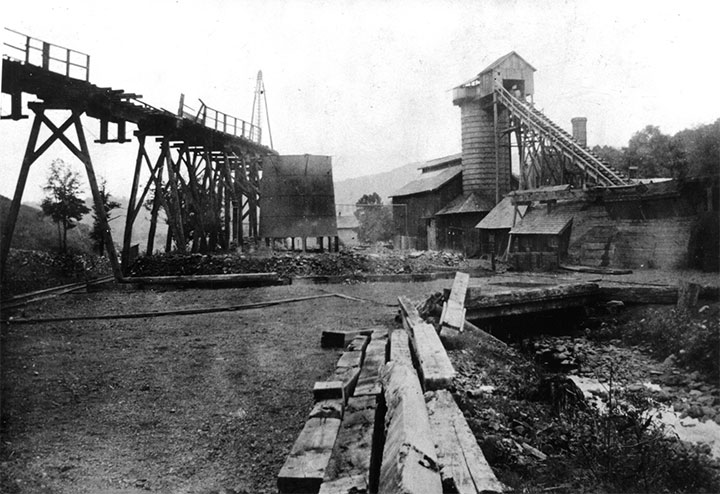

The ET&WNC had been built as an outlet to the world for Cranberry iron ore, which was considered the best magnetite iron in the United States at the time. With its isolation finally over, it was anticipated that there would be a huge demand for the ore. The owners of Cranberry Iron & Coal were all iron and coal men who had built the East Broad Top Railroad ten years before, and they thought they could make a greater profit by producing iron at the mine instead of hauling it out to civilization. In 1884, they “blew in” an iron furnace at Cranberry in the bottom below the open pit mine. Soon the area around the mine was a very busy place, with hundreds of men working to make iron.

The furnace was of the cool blast type, and produced a type of iron currently in vogue for many applications. Charcoal was used to provide the heat, and several beehive kilns were erected just south of the furnace. The railroad tracks ran through all this activity, and up to 10 percent of the ET&WNC platform car fleet can be seen in photos supporting the creation of charcoal. This made the mine very labor intensive, even in the low wage South. At one point over 500 men were at work in the mine area, and the furnace could only produce about 14 tons of iron a day, or a little over one platform carload.

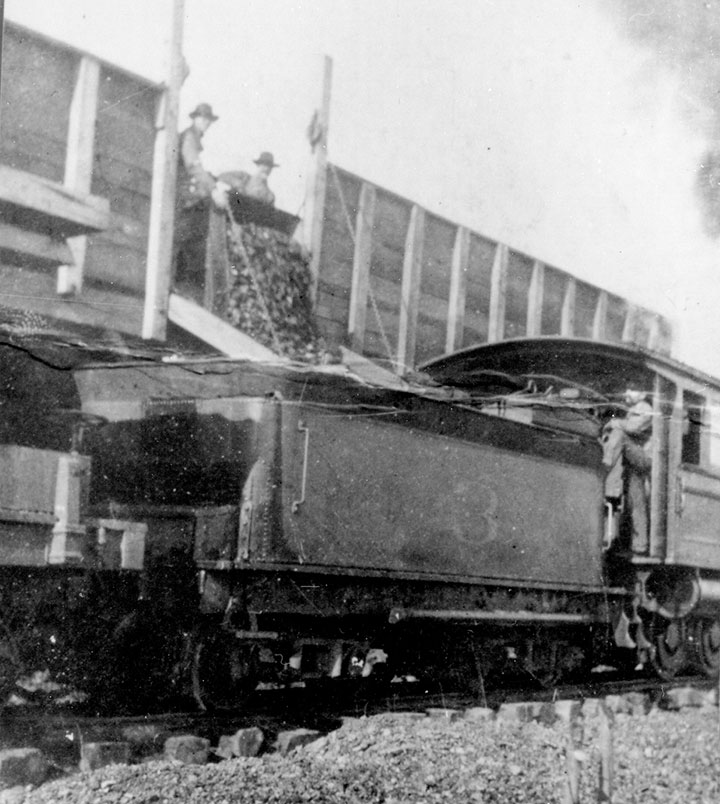

Around 1890, the furnace was converted to coke purchased off line and hauled in, lowering the cost but not making the furnace more profitable. Both the furnace and the mine were shut down for several years during the late 1890s. When the furnace converted to coke the railroad converted the locomotives from wood to coal, removed the large Radley and Hunter stacks replacing them with straight smokestacks changing the look of #3. In order to haul the coke and coal to Cranberry, the railroad had purchased 24 four-wheel ore cars from the Southern Car Works of Knoxville, Tennessee by mid 1891. They were able to handle more bulk than the low-sided gondolas, but did not track well, causing at least one accident on the railroad. These cars were moved to non-revenue service after knuckle couplers were installed, and they were eventually transferred to the mine.

I have found no photos showing #3 pulling a freight train, except for one in a private collection, but #3 was used regularly, during the years that the mine and the furnace were running at capacity. From the photos of activity at Cranberry, one locomotive would have been kept busy moving cars around that facility during the day. With only three locomotives on the roster, and two mixed passenger trains running during the good times, #3 would have been found anywhere on the railroad.

The low profits of the mine and furnace made the ET&WNC unprofitable as well. With the exception of a few years in the 1880s, the company could not even pay the interest on its 30-year mortgage. When things looked bleak, they got even worse. The May Tide (Flood) of 1901 washed out the railroad in dozens of places and stranded two trains in the Doe River Gorge. Edward Sisemore was the third engineer on the seniority list and he was one of the engineers stranded. By the records it appears that the engineers were assigned to specific locomotives, so #3 was stuck for several weeks while the one remaining locomotive worked to repair the line. It took six weeks to get trains running again, with temporary trestles replacing most of the bridges and several washed out sections of the Doe River Gorge.

Luckily for the railroad, some of the owners of the mine had formed a new company to lease and eventually purchase a more modern iron furnace in Johnson City. This furnace, under other owners, had started up in 1898 giving the railroad a lot of business hauling iron ore to Johnson City. When the new company took over the furnace, they leased the mine as well. The old furnace was not part of the deal and was torn down in 1907.

This new ore business and the building of the Linville River Railway in 1899 put new life into the ET&WNC. New locomotives and cars began to be purchased and put into service. Westinghouse air brakes and knuckle couplers were being installed at the time of the flood and they made it possible to pull more cars in a train. In order to increase business and take advantage of a coal rate war, the ET&WNC installed a standard gauge third rail between Johnson City and Elizabethton in 1904-1905. Number 3 was taken out of main line service and assigned switcher duties in Johnson City, where she shows up in most of the images that I have seen.

With newer locomotives being purchased almost every year, #3 was soon deemed surplus and put up for sale. She was sold to the Fosburgh Lumber Company in January 1911 and disappears from the public record. Fosburgh was headquartered in Norfolk, Virginia, and had logging operations in the White Oak Swamp at Gumberry, North Carolina. Number 3 had served the ET&WNC just shy of 30 years. She had seen the company go from optimism and great expectations, to the depths of flood damage and near bankruptcy, and back to a period of great optimism. The old locomotives from the 1880s had been replaced with new motive power, designed for specific jobs on the busy railroad. I will cover these locomotives in future issues of the Gazette.