In the first decade of the Twentieth Century, the world of the East Tennessee & Western North Carolina Railroad was figuratively turned upside down. For nearly twenty years, the company had struggled along, barely paying the bills but not always the bond payments, with a small handful of men keeping the trains running. While the national economy waxed and waned, the railroaders carried on, always thinking that things were going to be better “next year.” With the new century came new business opportunities, new locomotives, new freight cars, and new, to them, passenger cars. As I described in the January/February issue, the new Consolidations were moving lots of freight out of the mountains at a rate never before seen by this narrow gauge.

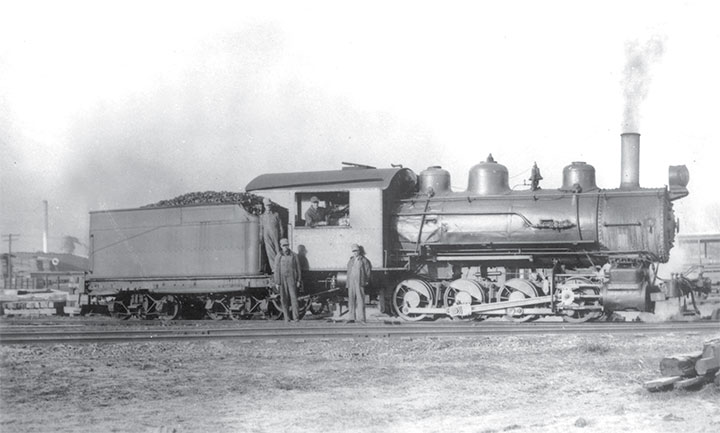

Photo, collection of Doug Walker or Ken March.

In 1904, the opportunity arose to incorporate bridge traffic over the railroad. The Virginia & Southwestern Railway had a standard gauge line that ran into Elizabethton, Tennessee, from Bristol, Virginia. They also had a line that ran deep into coal country in southwest Virginia. Coal moving south into Tennessee was handed over to the Southern Railway, which greatly increased the freight rate to towns just a few miles south of the state line, including Johnson City, the terminus of the ET&WNC. These towns bristled at the much higher charges and sought relief from any direction. The ET&WNC management wisely chose to add a standard gauge third rail between Johnson City and Elizabethton, which was completed in 1905. Standard gauge traffic could now be hauled over the line using unique swivel couplers mounted on the narrow gauge locomotives.

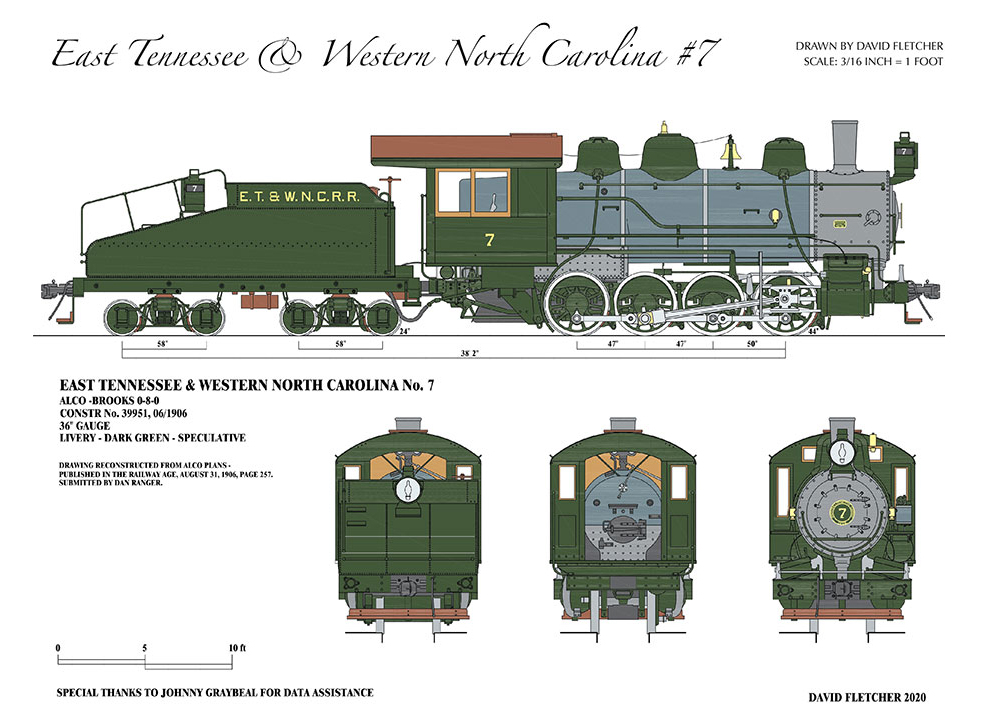

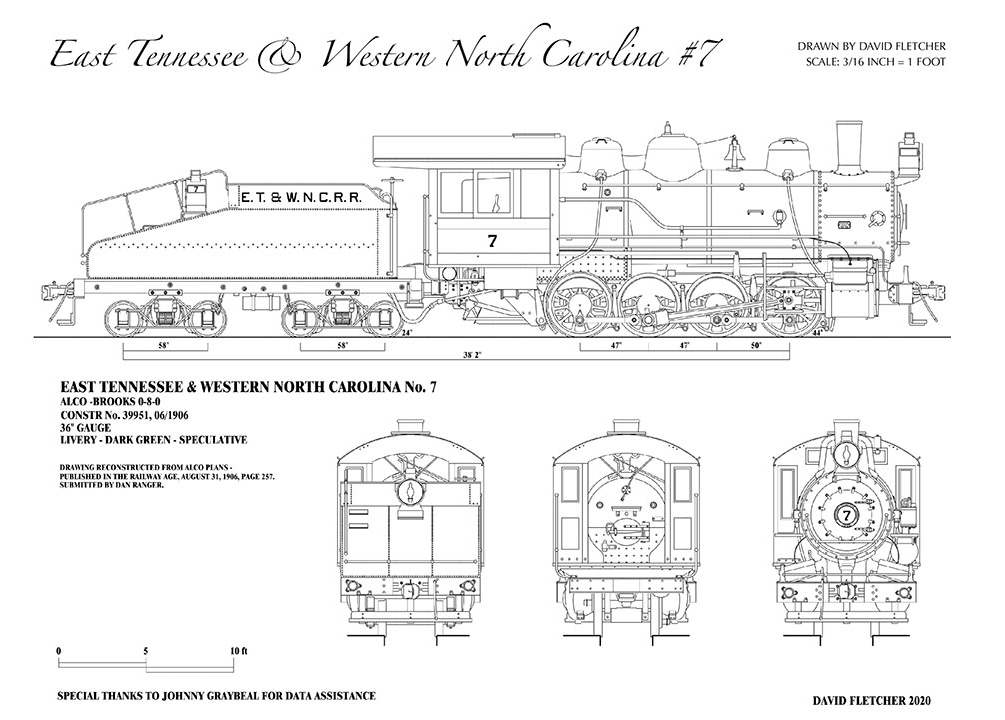

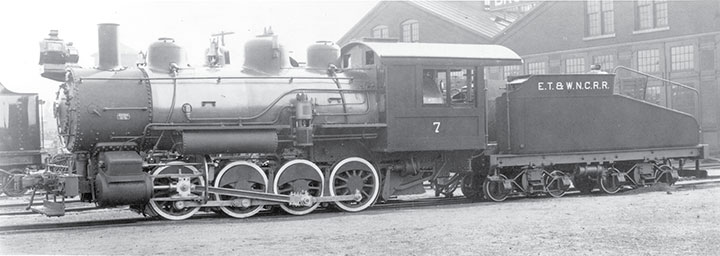

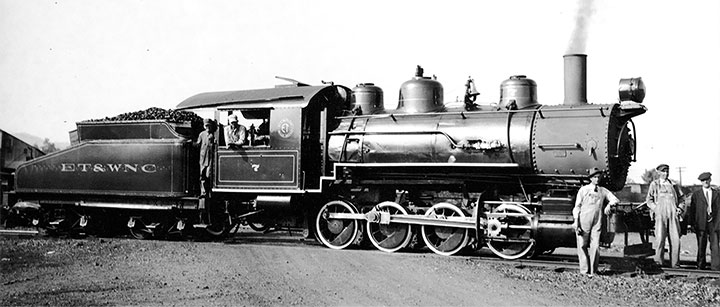

With freight backing up in both towns, the ET&WNC management chose in 1906 to purchase a switching locomotive to move this increasing tonnage around. Dedicated switchers were common on busy standard gauge railroads, but in the narrow gauge world they were usually an older road engine downgraded to switching duties. One would think that with increased standard gauge business they would have just bought a standard gauge locomotive, but they chose to stay with narrow gauge and use the swivel couplers. Rather than go to Baldwin, the usual source of ET&WNC power, the management turned to ALCO’s Brooks works for an 0-8-0 switcher based on their standard 0-6-0 design. ET&WNC #7 was basically a standard gauge locomotive with a narrow gauge frame, and an extra pair of drivers. To facilitate the narrower tread, the cylinders were canted inward so the main rods could connect with the drivers.

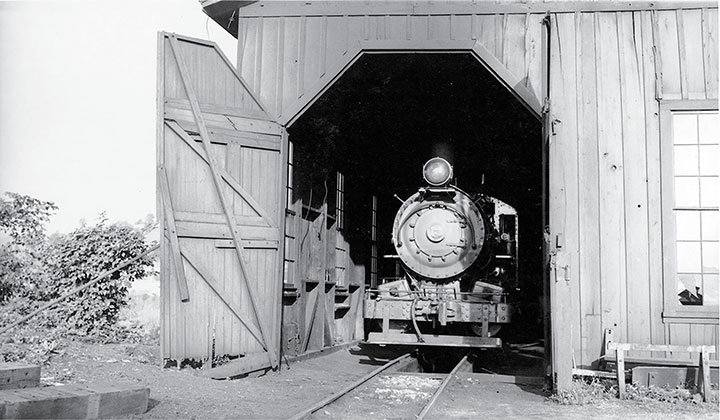

Number 7 immediately went to work in the busy railroad yards of the ET&WNC, as there was plenty to do. The ET&WNC interchanged with Southern Railway and the Clinchfield in Johnson City. The Southern connected at milepost 0, but the CC&O paralleled the ET&WNC from there to milepost 1. The yard tracks were all dual gauge, allowing plenty of space for transloading materials between the two gauges. There were numerous factories adjoining the yard which used lumber and wood products brought in from the mountains. There was a coal transfer trestle that was later purchased by the railroad, enlarged, and used to transload bulk coal, iron ore, and petroleum products. Beginning in 1908, a spur ran to the Cranberry furnace, which used whole trainloads of iron ore from the mine at Cranberry. Elizabethton was a growing city as well, with numerous industries served by the narrow gauge on dual gauge tracks. The Southern Railway purchased a large block of V&SW stock, and then outright leased the company in 1916, which effectively cut off the bridge business, but the railroad continued to get coal delivered to Elizabethton for delivery to their own locomotive coaling facility east of Elizabethton, known on company timetables as Coal Chute. Number 7 could thus be anywhere on the narrow gauge from milepost 0 to 11, over one-third of the total mileage. Timetables clearly stated that Yard Limits extended from Johnson City to Coal Chute, and late trains had to watch out for the switcher, which had right of way over late and non-timetable trains. Crews worked on average 12 or more hours a day to keep everyone served and cars moving. Number 7 did make at least one trip to Cranberry, which caused quite a stir in that mountain community. Seems it was the first time that a “broad gauge” locomotive had come up over the narrow gauge!

Photo, collection of Doug Walker.

It was claimed for decades that when #7 was built, it was the largest narrow gauge locomotive built for American use. That is not the case, however. The D&RG K-27s, built in 1903, were longer, had more weight on drivers, a larger boiler, all the figures that Ferroequinologists (students of the iron horse) use to determine “largest,” so the #7 claim has no validity. We can say however, that #7 was unique in many ways. ALCO used a version of the builder’s photo in ads, saying they could build switchers in any “practicable gauge,” but no one took them up on the offer. Railway Age did publish a drawing of the #7, making a big splash in the railroad world that month, but again, narrow gauge railroads had the used market to turn to for cheap power for switching. Number 7 was also the only narrow gauge 0-8-0 in American use. One 0-8-0 was built by Baldwin for a U.S. customer, but it was converted to a 2-8-0 at an early date, making #7 truly a one of a kind locomotive.

Photo, collection of Ed Bond.

Photo, collection of James McAteer.

That being said, #7 was extensively modified over the years. As originally delivered, the locomotive had 44-inch diameter drivers, making her able to make good speed as well as pull heavy loads. That swivel coupler on her front and rear allowed her to couple to cars of both gauges with the pull of a pin. When moving standard gauge cars however, that put the coupler alignment off center, which put a strain on the frame. After numerous problems with cracks in the frame, ALCO designed a new heavier frame for the #7 in 1924. The new arrangement utilized 36-inch diameter drivers, which added to the tractive effort, but reduced the speed. The sloped back tender was modified at this time, with the sides being built up to make it a square tender, holding more water. The wood cab was replaced by a steel cab as well.

In 1925, it was announced in the press that a huge rayon plant was to be built just west of Elizabethton. This was a blessing to the ET&WNC as narrow gauge traffic out of the mountains had begun to drop off sharply due to improved roads. Large shipments of building materials kept the switcher busy from the first day of construction. This plant opened in late 1926, and another facility started going up right beside it. The ET&WNC management decided that it was time to move up to a standard gauge locomotive, and bought #828, a 2-8-0 Consolidation from the Norfolk & Western Ry. This typical 2-8-0 was much larger than the “huge” narrow gauge #7, a testimony to the limits of narrow gauge. Number 828 was intended to replace #7 in switcher service, but it was not to be. Number 828 turned out to be the first “lemon” ever purchased second hand by the ET&WNC. The locomotive was often out of service and was sidelined as “Not Needed” in May 1931. She never returned to service. Number 7 went back to full time duty and soldiered on, moving more and more standard gauge cars.

Number 7 was a big locomotive, and it took a big man to handle her. Big John Lewis was the engineer on the switcher for many years, and was very adept at manhandling the Johnson bar, even under back head pressure. One day C.C. “Brownie” Allison, a relative of another engineer, was pulled out of high school classes to fill in for a sick crewmember. He might have still been in school, but he was already a qualified engineer, at least in this emergency. He was told to take #7 for the day. Brownie, being a small man, was dreading struggling with that reverser all day. Big John saw his dilemma and just pointed his big lunch box at Brownie, and then at another locomotive. Brownie gladly traded jobs with him, seniority list notwithstanding, leaving the big #7 to the big man.

Photo, collection of Doug Walker.

In 1936, #7 was one of the first locomotives painted in the new green paint scheme adopted by Master Mechanic Clarence Hobbs, which was based on the look of Southern Railway passenger locomotives. It was the first locomotive to receive the ET&WNC Railroad oval on the cab, but it was different from the one on the Ten Wheelers. The tender was modified again, returning it to the sloped back configuration, to facilitate backing movements now that water was available from a tank in front of the rayon plants.

Number 7 came out of service for repairs on September 14, 1938. This was done each year for an annual inspection per ICC regulations. An inspection of the interior of the boiler found pitting that was deemed too extensive to repair. Number 7 was retired and cut up for scrap in June 1939, ending a career that had lasted for 32 years.

Photo, collection of Doug Walker.

ET&WNC #7 does hold the distinction of being the most successful narrow gauge switching locomotive in U.S. service. She may have been the only one, but that does not take away from over 30 years of dependable daily, except Sunday, work. She kept the ET&WNC a narrow gauge only railroad for twenty years, and replaced her replacement. Once #7 was deemed unrepairable, the railroad moved swiftly to buy another used standard gauge locomotive to replace her. Number 204 arrived in January 1939, and began the process that allowed the narrow gauge ET&WNC to be abandoned in 1950, and convert the railroad into a standard gauge short line that lasted another half century.

Those wanting to model #7 in HOn3 do have an option. The old Roundhouse standard gauge 0-6-0 boiler looks similar to the #7’s boiler. The HOn3 Roundhouse 2-8-0 frame actually has the right diameter drivers. The tricky part is reproducing the canted cylinders of the prototype, but it has been done. The Roundhouse HOn3 tender will work for the 1924–36 version of the tender. Some work will need to be done to accurately reproduce the extended cab roof.