The East Tennessee & Western North Carolina Railroad was experiencing a boom in the first decade of the Twentieth Century. After 20 years of very mediocre operations, the stars were finally aligning for the little narrow gauge railroad into the heart of the Blue Ridge Mountains. The freight business was booming, and it seemed that every month there was a new business wanting service from the railroad. With more industry came more people needing to travel back and forth over the line. The automobile was still a novelty in the major cities, so the train was the only reliable way to get around. Railroads nationally were in a Golden Age of service, and the ET&WNC wanted to join in that boom.

-Photo, collection of Ed Bond.

-Photo, collection of Mary Hardin Cowen.

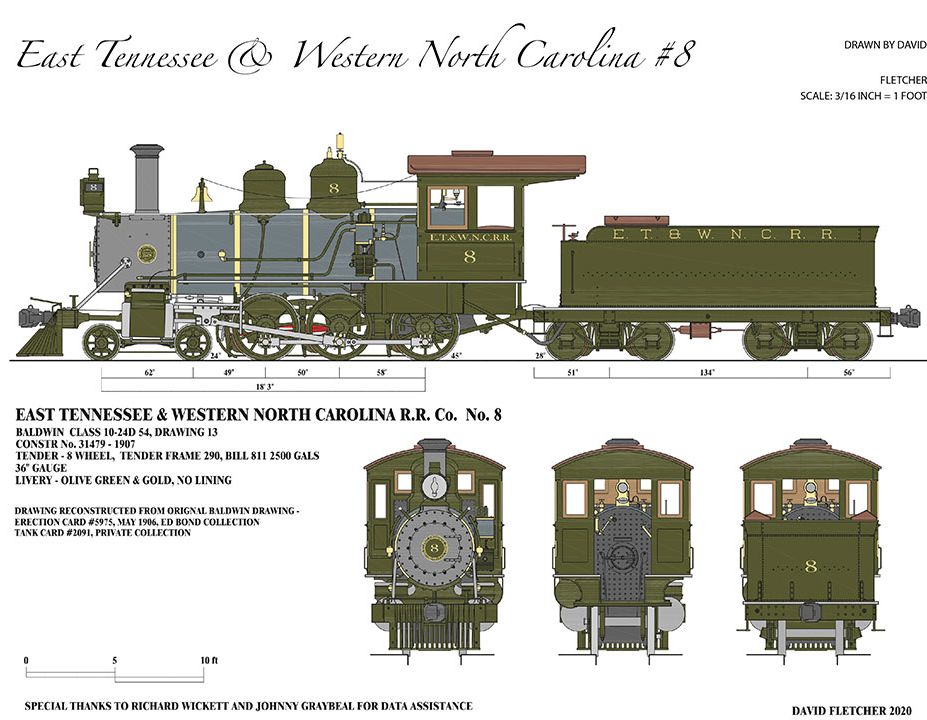

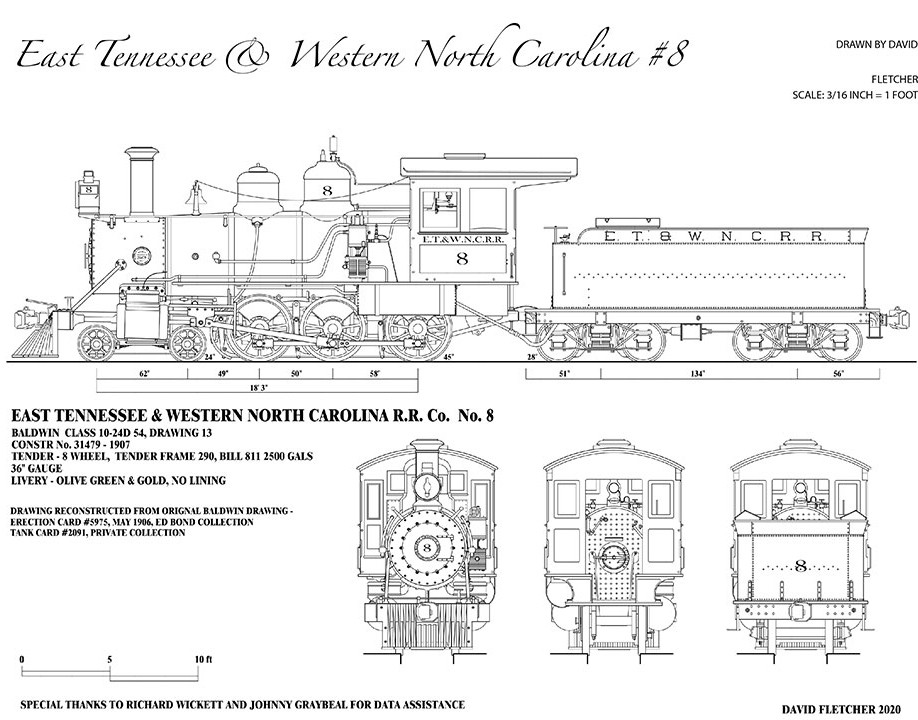

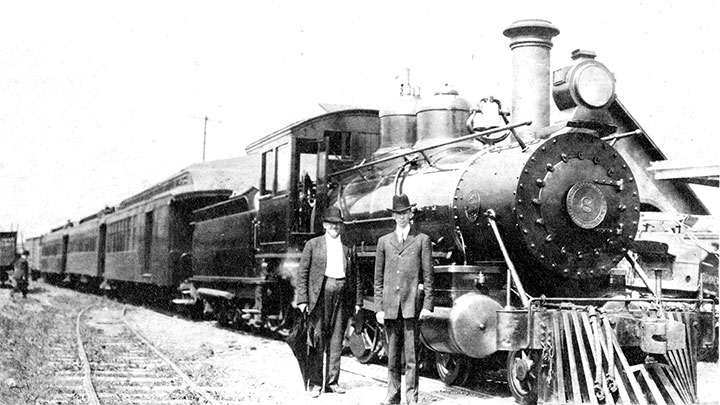

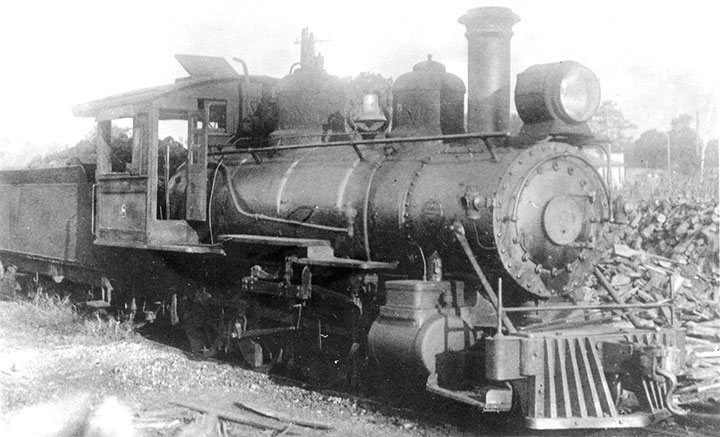

It had begun with the purchase of some surplus passenger cars from the Carolina & North-Western and Lancaster & Chester, both narrow gauge lines which had standard gauged by 1902. Five cars were purchased in 1903, which became ET&WNC combine 6, coaches 3, 4, and 7, plus a parlor car called Ethel. This one purchase almost tripled the ET&WNC passenger car fleet, finally providing enough seats for large groups of tourists who were discovering the scenic beauty of the Blue Ridge Mountains for the first time. In order to provide quick service between Johnson City, Tennessee, and Cranberry, North Carolina, the railroad turned to their main locomotive supplier, Baldwin Locomotive Works, for a dedicated passenger engine. Baldwin promptly offered them a copy of a proven design that had been done for the Nevada-California-Oregon Railroad, drawing number 13 of Baldwin classification 10-24D. This drawing was used to provide locomotives for several companies on both sides of the Rio Grande, with a total of 18 engines being delivered between 1903 and 1925.

-Photo, collection of Ed Bond.

-Photo, collection of Cy Crumley.

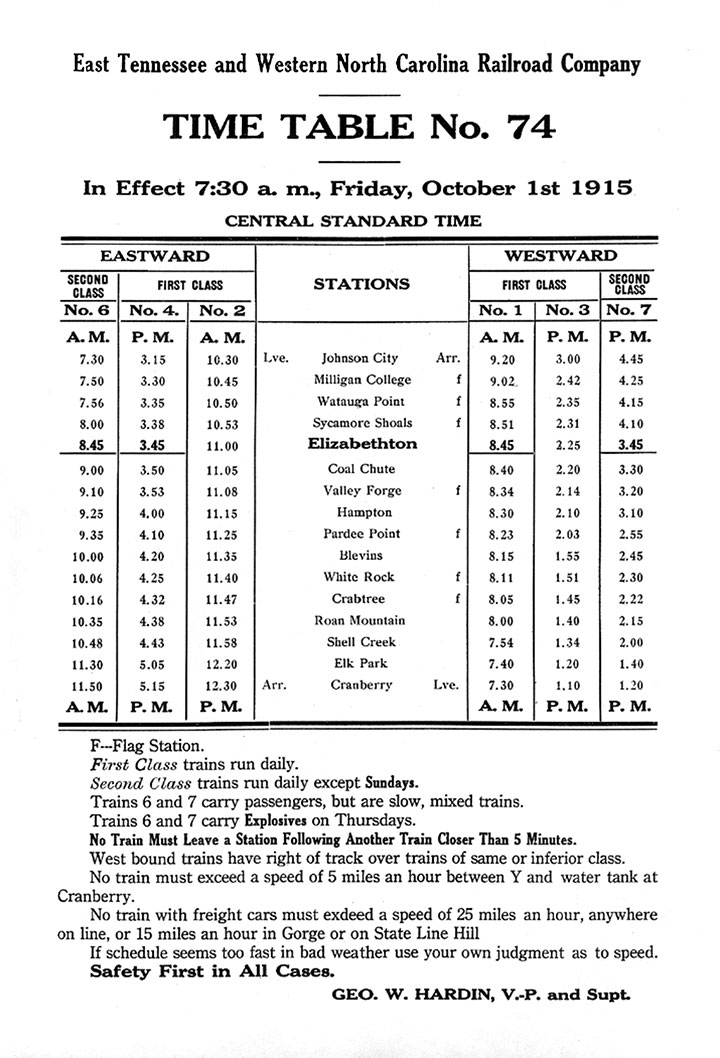

The ET&WNC was only 34 miles long. So, #8 with those high (for narrow gauge) 45-inch-diameter drivers could make good time, and the higher boiler pressure (180 lbs.) gave the #8 good acceleration as well. It was found that the locomotive could move a train over the line in less than two hours. Instead of two train sets making their way over the railroad and meeting in the middle, #8 was able to run back and forth and make up to two round trips per day with only one crew. This made the passenger timetables look full and busy, but it was really just one train set making multiple runs per day.

The ET&WNC settled into a pattern that lasted for several years. Trains left Cranberry first thing in the morning for Johnson City, and returned almost immediately. The pattern was repeated again in the afternoon, creating an almost commuter train like pattern along the entire railroad. It was very popular with people wanting to do business in one town and then return home in less than a day. The Linville River Railway was running by this time, and they used their Shay to make the 12 mile run out from Pineola to Cranberry twice per day, mostly for the tourist traffic. Newspaper accounts from that time suggest that the LR train was often tardy in getting to Cranberry, but there was always another train to Johnson City a few hours later to make a connection.

-Photo, collection Tweetsie Railroad.

This pattern continued even after the Linville River Railway was purchased by Cranberry Iron & Coal in April 1913. Track gangs spent the next few years rebuilding this common carrier logging line to the higher standards of the ET&WNC. A tourist enclave existed at Pineola and another resort was at Linville, just two miles by track from Montezuma. Well to do tourists enjoyed riding in the parlor car Azalea, which was purchased in 1912 after the Ethel was destroyed in a coach shed fire in 1907. Beginning in late 1915, the LR began an extension to Shulls Mills in Watauga County, to serve a sawmill there. This new construction took over a year to be fully completed, and while that was underway, First Class run through passenger service began to Pineola in 1917. Adding 12 more miles to the trip reduced the number of trips that could be made per day, but it was a great improvement over the slow LR mixed train. First Class service would be extended to Shulls Mills in the spring of 1918.

-Photo, collection Gerald Ledford.

This put the combined ET&WNC/LR passenger train running 56 miles each way, a far cry from the 34-mile-long ET&WNC. An entire day was required to make the round trip. Add to this the fact that the new line crossed the Eastern Continental Divide not once, but twice, between Montezuma and Shulls Mills, incorporating several miles of 4 percent grade, and it becomes clear why the train was taking much longer to make the trip over the whole railroad system. The ET&WNC purchased a three car set of new enclosed vestibule passenger cars from American Car & Foundry’s Jackson & Sharpe plant in November 1917. Built to visually match the Azalea, these cars brought true First Class service to the mountains. They were significantly heavier than a typical narrow gauge passenger car, incorporating steel frame construction with wood sheathing over the frame. There are photos of #8 pulling the new train set but it must have been a strain on the locomotive, as newer larger Ten Wheelers were assigned the long distance trains.

-Photo, collection Mike Dowdy.

-Photo, Mike Hardin Collection.

The Linville River Railway completed its final extension in early 1919 to Boone, North Carolina. This became the eastern end of the narrow gauge system. Boone had been trying to get rail service for 40 years and was excited about all the business that would come to the town via the train. The original schedule had the train leaving Boone first thing in the morning heading to Johnson City, returning late in the afternoon. In June, a second train was added, leaving Johnson City in the morning running to Boone and returning late in the day. Number 8 was assigned to this second shorter train, which was usually just a combine and a coach. Unfortunately, the Town of Boone at that time could not support a second train and it was dropped after only a few months. For the first time in 13 years, #8 was out of a job.

The ET&WNC had a dedicated coaling facility called Coal Chute just east of Elizabethton. ET&WNC coal chute records after 1919 still exist and are available for study. Those monthly reports show how much coal each locomotive received each day as it passed by. Number 8 is shown as taking coal only three times in the entire year of 1920 and does not take coal again until 1924. It is possible that the locomotive worked on the Linville River side of the system but that is doubtful, as all of the LR mileage during this time was mixed train mileage, which #8 was not designed to handle. During this time someone built a homemade whistle for #8, consisting of three metal tubes, which undoubtedly made a unique sound when blown. The ET&WNC initiated a commuter service between Johnson City and Elizabethton in July 1924. A gasoline powered jitney coach was to be the main power for this run, but a locomotive and train often filled in due to breakdowns or high demand. Number 8 did pull a few of these trains, but even before the service ended in January 1925 due to the opening of a competing paved highway, #8 had been sold.

-Photo, collection Doug Walker.

The ET&WNC sold #8 in October 1924 to Gray Lumber Company in Waverly, Virginia. At first glance that seems odd, but Gray Lumber owned other Ten Wheelers so #8 fit right in. The purchasers even sent after the unique whistle, which the crews had kept in Tennessee. Number 8 served in obscurity in Virginia for the next three decades. It is not known exactly when she went out of service, but she was still around in the mid-Fifties, when railroad fan Doug Walker was able to save the throttle before the locomotive was scrapped. The number plate was preserved as well by H. Reid and is now in a private collection.

The “Little 8” had a profound impact on the ET&WNC. The locomotive gave the company the ability to cater to passengers in a timely and efficient manner. The 4-6-0 wheel arrangement proved to be a perfect match for the grades and speeds of the ET&WNC, and all of their new purchases in the years to come would be Ten Wheelers. She was the last ET engine to be sold to another company for further use as long as the narrow gauge ran. Considering that she lasted until the 1950s, it is a testimony to the strength and “spirit” of a locomotive. The ET&WNC old timers remembered her fondly.