By the end of the first decade of the Twentieth Century, the East Tennessee & Western North Carolina Railroad had finally come into its own as a progressive narrow gauge railroad. Hopper cars of iron ore were being transported from the mine at Cranberry to an iron furnace in Johnson City in greater and greater numbers. The population in the region was growing, and tourism was becoming a major contributor to the coffers of the company. Lumber shipments were also on the increase, giving even more tonnage to the railroad. The ET&WNC had used locomotive designs developed for other railroads since its earliest days. With business continuing to grow on this single track railroad, the pace of transportation needed to increase. With very few narrow gauge engines being constructed for U.S. companies, the ET&WNC decided to pursue a new way to move the freight.

-Photo, Keith Holley Collection.

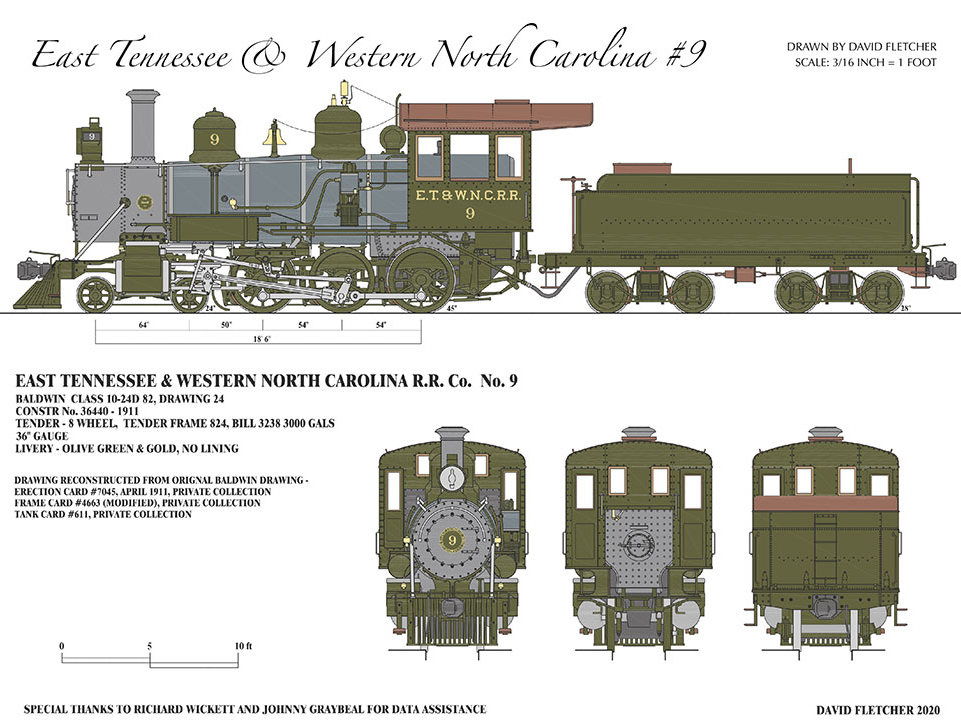

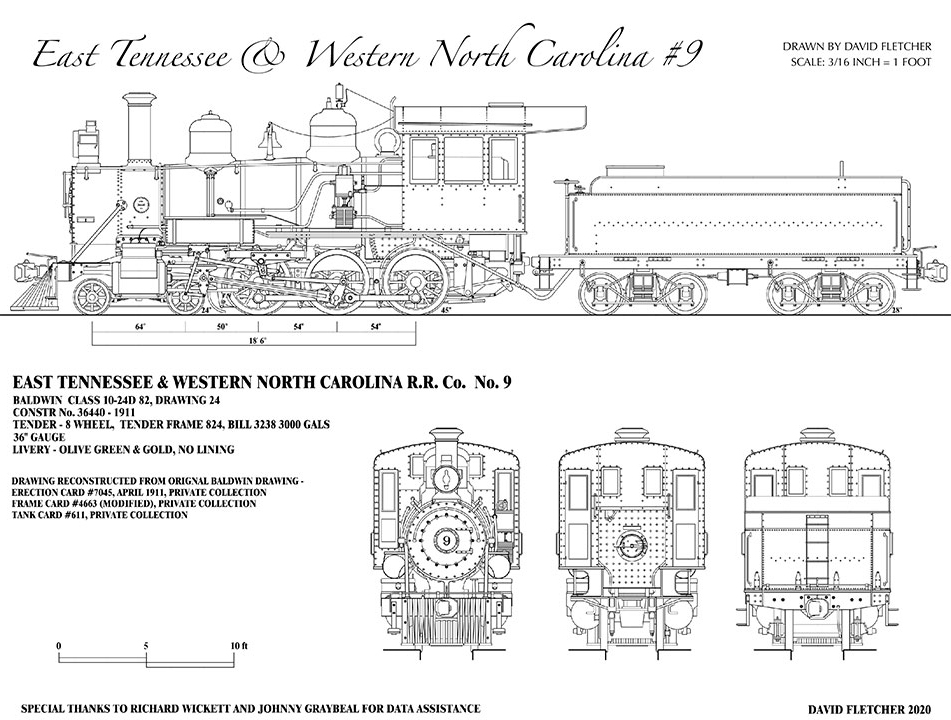

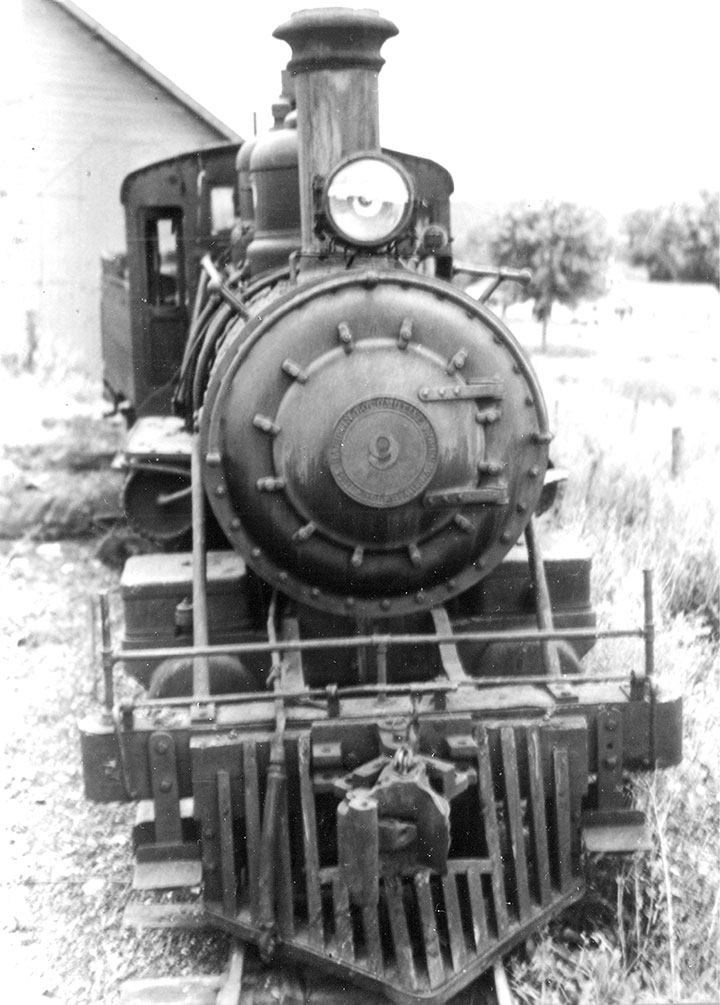

In 1911, they went to Baldwin Locomotive Works looking for a new locomotive to pull a morning train that brought iron ore to Johnson City each morning along with passenger cars, requiring strength as well as speed. Baldwin replied with the 10-26D 42 drawing originally done for the Nevada-California-Oregon Ten Wheelers. This new design was in the 10-24D class, meaning slightly smaller cylinder diameter, but the larger size and 45-inch drivers meant more power at speed on the railroad. The ET&WNC management approved the design and Ten Wheeler #9 was built in April, 1911. This locomotive was larger and more powerful than #8, which continued to be used on the daily passenger trains.

-Photo, H.L. Broadbelt Collection.

The initial assignment for #9 was the train referred to locally as the Cranberry Local. This train left Cranberry, North Carolina, each morning with enough hopper cars loaded with Cranberry iron ore to supply the Cranberry Furnace in Johnson City for one day, along with at least one passenger car. This Second Class train was thus on the passenger timetables and had priority over the railroad in the early morning hours. Iron furnaces operate 24 hours a day, seven days a week, when in blast, so the Cranberry Local was the conveyor belt that kept the furnace, the mine, and the whole organization actually working smoothly. It also gave passengers yet another opportunity to get over the railroad. Number 9 would reign supreme as the fastest, most powerful locomotive on the railroad for the next five years.

-Photo, Curtis Brookshire Collection.

The success of #9 prompted the management to seek even more performance from their locomotive fleet. They went back to Baldwin in late 1915 and ordered a slightly scaled up version. Numbers 10 and 11 were delivered early in 1916. These locomotives were the beginning of the perfect fleet of Ten Wheelers for the ET&WNC. More on them next issue. As these locomotives came online, they took over the Cranberry Local and other fast freight duties. This was fortuitous, as things were changing on the narrow gauge and #9 was needed elsewhere.

The Linville River Railway had fallen under the Cranberry Iron & Coal properties’ umbrella in April, 1913. As this former lumber line was upgraded, the regular passenger train was extended first to Pineola, and later to Shulls Mills as the LR Ry. was extended. With the new locomotives, came new enclosed vestibule passenger cars in November, 1917. The additional distance and the added weight of the new steel/wood-sided cars was too much for #8. The extension of the mainline on to the town of Boone in early 1919 made it clear that larger locomotives would need to handle the daily First Class passenger train. Number 9 easily fell into this role.

-Photo, Mike Dowdy Collection.

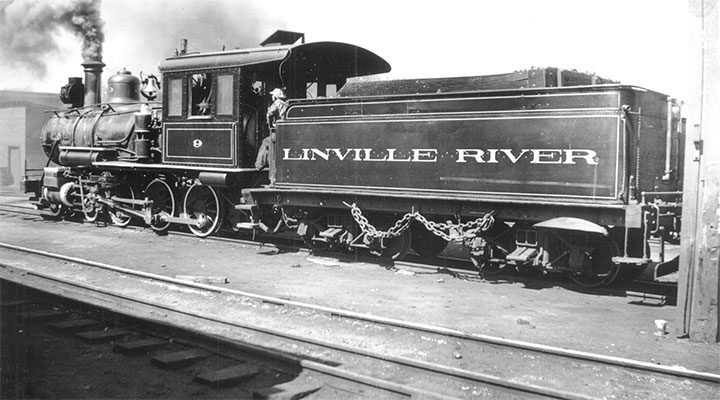

By this point, #9 had another owner. As bigger Ten Wheelers came on board, the older engines in the ET&WNC stable were sold to the Linville River Ry. Number 9 was transferred in October, 1917, though she retained her E.T. & W.N.C.R.R. lettering on the cab until at least 1919. This gave the Linville River a modern locomotive with relatively few miles on her. She would serve that railroad as long as it ran.

In the early 1920s, there were two First Class trains that plied the rails of the ET&WNC each day. One of these was Train 1/4, which pulled out of Boone early each morning and arrived in Johnson City in time to meet the daily trains on the Southern and Clinchfield railroads. It returned in the afternoon after a two hour layover. Coal usage records survive from the spring of 1920, and these records show how much coal was taken on a day to day basis by each engine that passed the facility. From 1920 to 1927, #9 spent over 95 percent of her time on this one train. In some months, the locomotive literally ran 31 days a month. That was a neat trick considering that the Interstate Commerce Commission required an inspection each month, including a boiler wash. Number 9, under the expert hand of engineer Sherman Pippin, would pull into Johnson City in time to meet the other trains. The engine would be uncoupled and sent to the engine house in the main yard. The shop crew would go to work while another locomotive went back to Boone that afternoon. The boiler would be washed out and all of the inspections done by lunchtime the next day, and #9 would go back out on the road with the afternoon train. Thus #9 would technically run 31 days a month.

-Photo, Bob Brown Collection.

These same coal reports showed another positive feature of #9. She used less coal than the larger Ten Wheelers she worked alongside. Ten Wheeler #12 pulled the other passenger train (2/3) regularly during that time, but it only ran from Johnson City to Pineola and back. Pulling a longer train with more cars, over a longer distance, #9 used up to a ton less coal per day. Some of that could be attributed to an excellent engineer and fireman working well together, but when #9 did have to be out, the replacement engine used more coal on the same tonnage. It is clear that #9 was the perfect locomotive for the First Class varnish on the ET&WNC/LR system. The coal reports changed in 1927 and stopped listing the engine number, so we are not sure how much longer #9 continued on this run. This was about the time that pure passenger trains were discontinued and all trains on the ET&WNC/LR became mixed freight and passenger. With tonnage becoming variable on a daily basis, it paid to let one of the larger Ten Wheelers handle the daily except Sunday Mixed.

-Photo by Vince Ryan.

By the mid 1930s, #9 had little to do on the railroad. By the end of 1936, she was the last locomotive on the LR roster, after the Consolidations were cut up for scrap. She was involved in a derailment in 1937, when she turned over and down a bank on the Hodges Gap grade, a few miles west of Boone. It took a lot of work to get her up and repaired. One of the results of this derailment was a fresh paint job and lettering scheme. For over 17 years she had carried black paint and simple L.R. Ry lettering in gold leaf on the side of the cab for company identification. Now, there was fresh black paint and white LINVILLE RIVER lettering and striping on the tender. This was the period of green paint and gold ET&WNC lettering on the other engines, so #9 was very distinctive.

-Photo, Curtis Brookshire Collection.

A pretty paint job does not guarantee you more work to do. There are records of the ET&WNC paying rental of 10 cents per mile for using #9 from April, 1937, through August, 1940, but this varied from 68 miles in August, 1938, to 1,088 in September, 1937. She did do yeoman service in special duty at the ET&WNC’s creosote plant at the Cranberry engine house. One of the locomotive inspection pits was filled with creosote to treat narrow gauge railroad ties. A steam line attached to the boiler would heat the stinking mixture for dipping. To avoid ICC inspections, the side rods would be removed from the drivers, proving the #9 was not in service.

Number 9 was in service on August 13, 1940, the day a disastrous flood washed out the Linville River Ry. She had left Boone that morning as always, but the water was so high in places that the crew wondered if they would make it. After a two hour layover in Johnson City, they started back to Boone but didn’t get far past Cranberry. The decision was made almost immediately to not rebuild, and permission to abandon the Linville River Ry came in 1941. Number 9 was sold back to the ET&WNC in July of that year. She was not used, and plans were made to scrap her once the other engines got a complete overhaul.

-Photo, Curtis Brookshire Collection.

World War II intervened. Two of the larger Ten Wheelers were sold to the War Department for use in Alaska, leaving only three narrow gauge locomotives left on the ET&WNC. The rayon plants in Elizabethton, Tennessee, were vital to the war effort, and the ET&WNC provided commuter train service to three shifts of plant workers and the local high school. The trains made three round trips between Elizabethton and Cranberry daily, which required two locomotives and crews. The photos from this period show #9 on the front of many passenger trains.

-Photo, C.K. Marsh Jr. Collection.

After the war, time was running out for #9. Narrow gauge operations were moved to Elizabethton in September, 1946, right after the engine received an overhaul. Material and coal usage records show minor repairs and work done on #9 up to April, 1947. After that, she sat on a sidetrack and rusted. The final run of the ET&WNC narrow gauge was October 16, 1950. Insurance was dropped on #9 on August 14, 1951, confirming that the engine had been completely scrapped by that date. The number plate and whistle were saved. The plate is in the hands of a private collector, but the whistle has been acquired by the Southeast Narrow Gauge & Shortline Museum and is on display there. Visitors to the 41st National Narrow Gauge Convention, September 1–4, 2021, can see an exhibit dedicated to this locomotive.