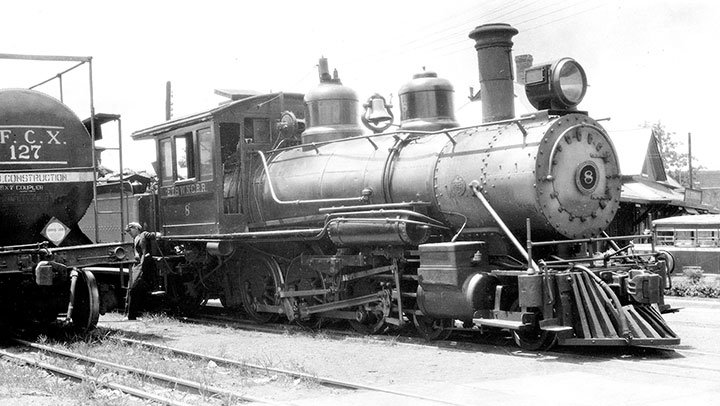

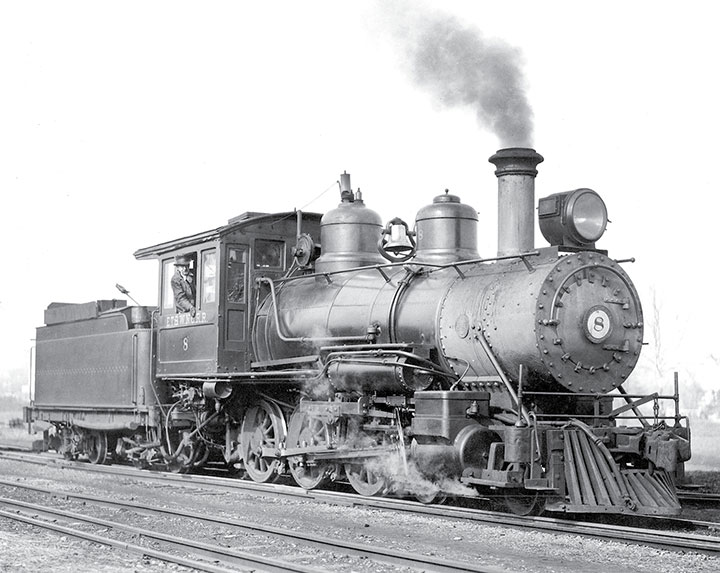

As I mentioned earlier in this series, the year 1924 was the peak of the financial fortunes of the East Tennessee & Western North Carolina Railroad/Linville River Railway system. Business was spiking both in passengers and freight. The railroad needed more motive power, but instead of purchasing another new Ten-Wheeler from Baldwin Locomotive Works, they once again turned to the used locomotive market. Turns out a twin sister of ET&WNC #9 had just become available. Let’s begin with the origins of the engine that became ET&WNC 2nd Number 8.

-Photo collection of Larry Smith.

The story begins in May 1909 with construction beginning on the Hampshire Southern Railroad, a standard gauge line that would run 38.5 miles between Romney, West Virginia, and Petersburg, West Virginia. The HS RR was completed by February 27, 1911, and soon taken over by the Baltimore & Ohio. It ran through an area of West Virginia that was perfect for fruit tree farming. Orchards with 50,000 trees were planted near this railroad. On May 26, 1911, a group of businessmen received a charter for the Twin Mountain & Potomac Railroad, which was projected to run from a junction with the HS at McNeill (Old Fields, West Virginia) in Hardy County, up Anderson Run (run is a Virginia term for creek) and over the ridge, then follow Patterson Creek north to a point near the Twin Mountain Post Office in Grant County, a total of 10 miles. The organizers owned the Twin Mountain Orchards, which was in the process of planting 1,500 acres of fruit trees and wanted to have railroad services. The orchard would be the parent company of the railroad, owning most of the preferred and common stock.

-Photo, collection of Larry Smith.

-Photo, collection of Larry Smith.

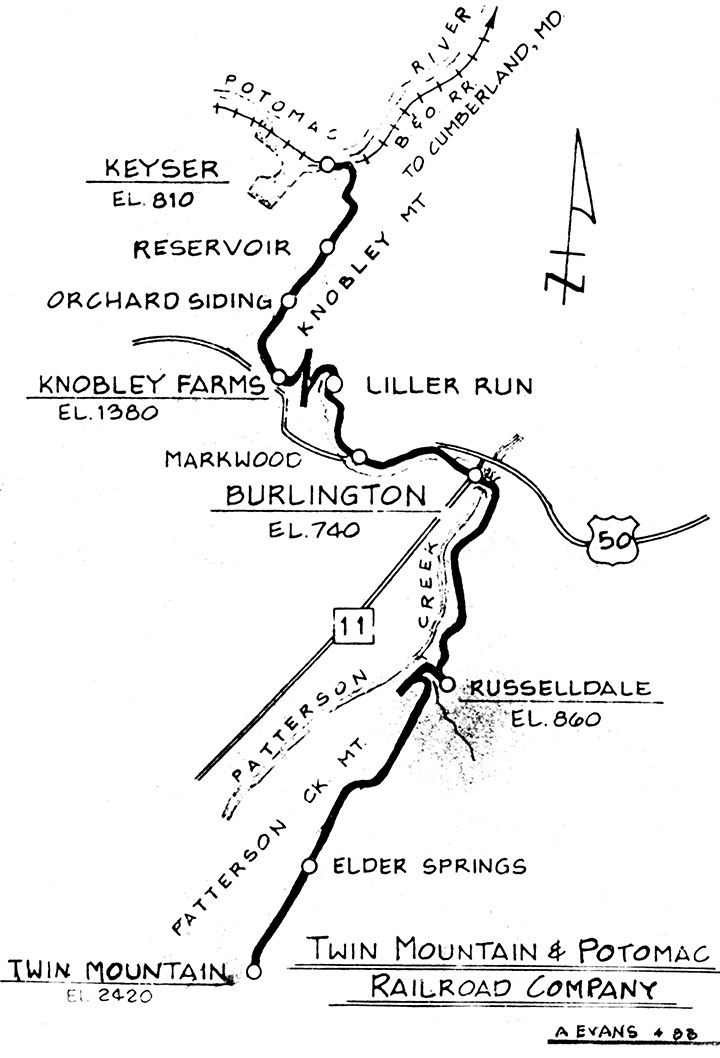

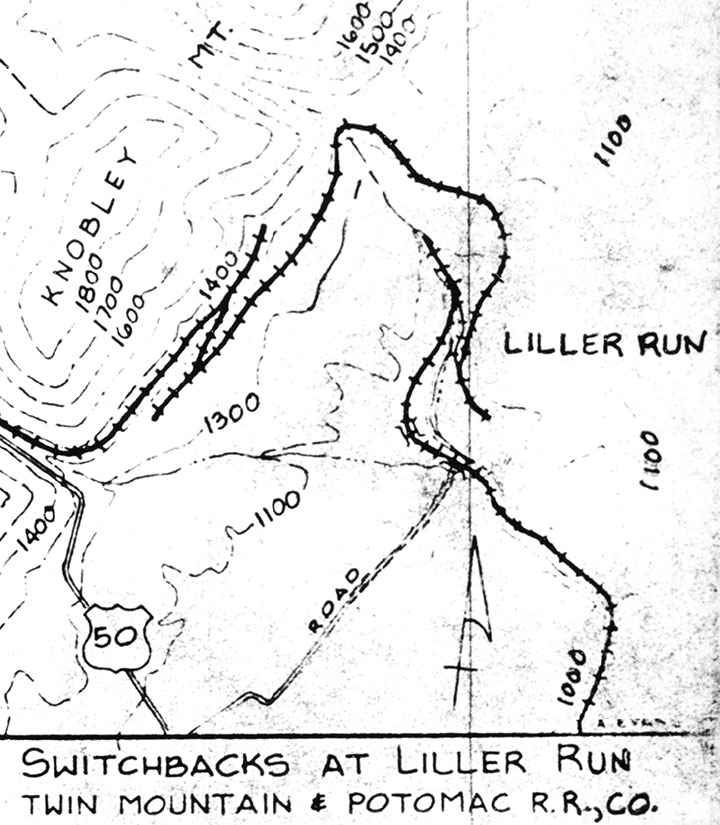

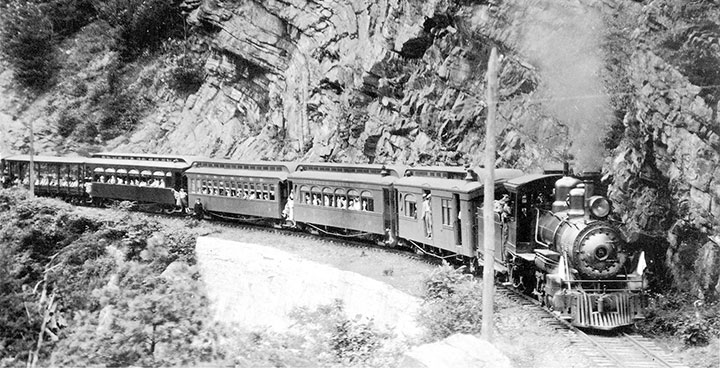

Ten days later, an article in the Washington DC Evening Star stated that this new railroad was now going to run from Keyser, West Virginia, on the B&O, up and over Knobley Mountain to Burlington, West Virginia, then extend southward to Twin Mountain, a total of 26.6 miles. The change in route came because of a mass meeting held on June 3rd, where the citizens south of Keyser promised to provide the right of way free of charge. One even offered to provide the cross ties through his property free of charge if the railroad ran that way. Once surveyed, this new route required two sets of double switchbacks to get down to Burlington from the top of Knobley Mountain. Another switchback was necessary to get to the orchards at Twin Mountain. Three foot gauge was chosen to make the double switchback route physically viable. The TM&P opened from Keyser to Burlington on August 16, 1912, and to Twin Mountain on March 13, 1913.

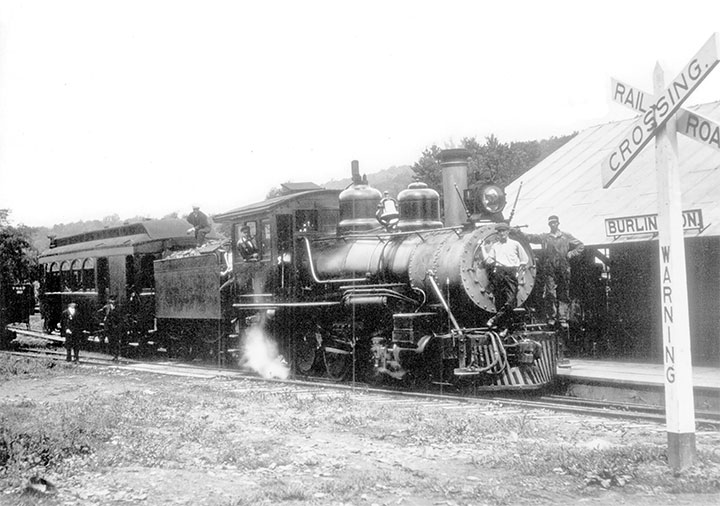

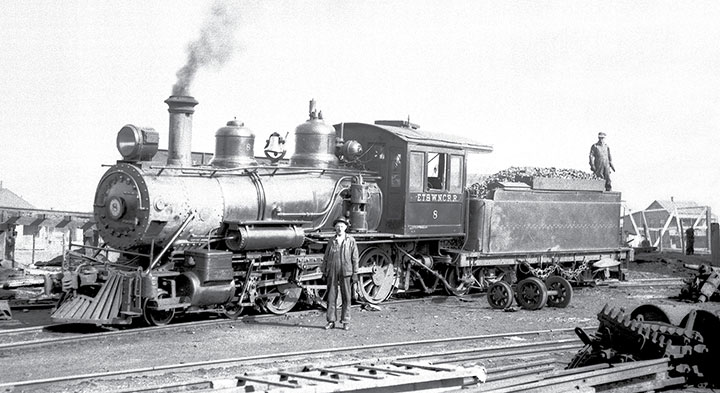

Economies were taken with the route, but the new management was so confident in the future of the line that they purchased all new equipment. This included new rails, new spikes, new passenger and freight cars, and two new locomotives from Baldwin Locomotive Works. An inquiry was made to Baldwin on October 5, 1911, for modern motive power at a reasonable price. Baldwin had produced ET&WNC Number 9 in April, so the TM&P ordered two copies of the design. Numbered 1 and 2, the engines varied from ET #9 in having wood cabs instead of steel and American Iron boiler jackets instead of the more expensive Planished jacket used on #9. At the time Ten Wheelers were associated with speed and pulling power, so the management obviously planned for their railroad to have fast service, even with multiple switchbacks. An article in the Baltimore Sun on August 4, 1912, when the first six miles of the railroad was opened with an excursion to Knobley Mountain, said that Mineral County (the northern part of the line) had 145 fruit growers, with 200,000 apple trees in the ground and 300,000 peach trees. Twin Mountain Orchards alone was planting 150,000 trees.

-Photo, collection of Larry Smith.

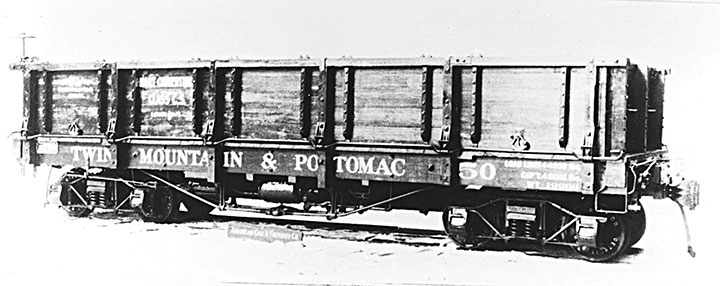

The TM&P had grand plans, but problems beset them from the very beginning. A lawsuit was filed against them when they used part of a county road for construction and did not replace it in kind. The suit dragged on for over a year, hurting the railroad’s reputation in the community. The fruit growers talked of canning operations along the railroad, but it never happened, making its main line haul-fruit a very seasonal operation, as peaches ripen in the summer and apples in the fall. In November 1916, near the end of the busy season of the railroad, a regional coal shortage shut down the railroad for days at a time. In February 1917, a heavy snowstorm dumped 35 inches of snow on the region, again closing the railroad. The largest online customers besides the parent company were only a few miles south of Keyser, so most shipments were short. The railroad owned a total of seven boxcars, 10 gondolas and one flat, not much for a business that would see high demand for cars at peak times (the ET&WNC in its early years had 10 boxcars and 64 platform cars for 34 miles). The closeness to Keyser and the B&O made truck haulage a major competitor, even at this early date.

The biggest headache for the railroad was the United States entry into World War One. Within months, the U.S. Government took over the major railroads. Under their control, the mainline companies were told what to haul and how much of it to haul. Little lines like the TM&P were shut out from coal deliveries, and empty freight cars for fruit to be shipped on to eastern markets were a low priority. The peach crop failed in 1918, and reduced manpower due to the war, hurt the apple crop. To add insult to injury, the charter had been given in 1911 without the usual clause excluding the short line from property taxes, creating yet another bill the railroad could not pay. The railroad lost money from the very beginning, and the taxes went unpaid for years. Poors Manual has listings for the TM&P for the years 1914 through 1919. Only two years show the all-important figures for profit and loss. By the year ending June 30, 1916, the TM&P had built up a running deficit of $125,177. All these factors doomed the Twin Mountain & Potomac. By February 1919, the railroad had shut down. An appeal to the B&O to take over and operate the line was denied by the government, which was still in control of the railroads. A receiver was appointed in November 1919, essentially to sell off the assets of the company. The West Virginia Timber Company purchased the rails, one locomotive and the ten or so cars left on the railroad in July 1920.

The West Virginia Timber Company had operations from Virginia to Arizona, cutting timber and operating oil wells. In Virginia, a new operation near Orange resulted in the building of the Rapidan Railroad in 1921, and presumably used the materials purchased from the TM&P. A search on Newspapers.com turned up very little about the Rapidan Railroad, other than it operated from 1921 to 1924, and ran from Orange to Rapidan (now Wolftown) Virginia. The timber was in the mountains, and the mill was at Orange, with standard gauge connections to the outside world. After only four years of operation, the lumber was declared to be of low quality, and the railroad was shut down. The former TM&P locomotive and passenger cars found a ready buyer in the reasonably nearby ET&WNC.

-Photo, collection of David Fletcher.

-Photo, collection of Larry Smith.

-Photo, collection of Mike Dowdy.

-Photo, collection of Gary Scoggins.

-Photo, collection of Doug Walker.

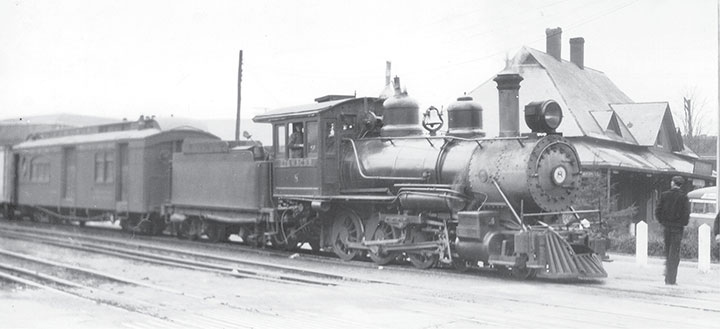

In October 1924, the ET&WNC sold their #8 Ten-Wheeler to the Gray Lumber Company in Waverly, Virginia, for $5,500. Two months later, they purchased the former TM&P equipment for $5,260.19. The engine and cars arrived in Tennessee in January 1925, and the shop forces spent the next five months rehabilitating them for service on the ET&WNC, spending another $1,706.67. The ET&WNC sold the combine to the Linville River for $2,100, so after all was said and done, the company got a locomotive and an enclosed vestibule coach and still had $633.14 profit in the bank. As the old #8 had been too small to use with the enclosed vestibule equipment, and the new #8 was an exact duplicate for the very efficient #9, the exchange was a very good deal for the ET&WNC.

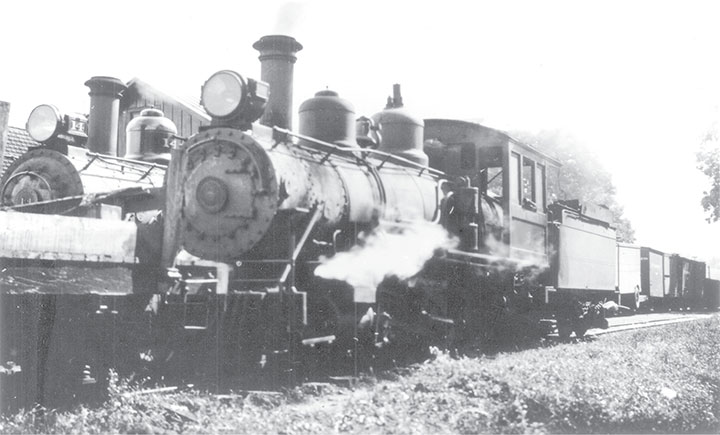

The 2nd #8 (hereafter simply referred to as #8) begins showing up on ET&WNC coal reports in November 1925. Things had changed drastically in the ten months the locomotive had been on the property. The near record numbers for passengers in 1924 had been cut in half by new highway competition, and more roads were under construction. Narrow gauge freight out of the mountains had dropped off significantly as well, in a trend that never reversed. The one bright spot in the traffic picture was the building of not one, but two rayon plants along the dual gauge section of the ET&WNC, which began in late 1925, about the time #8 entered service. This construction kept the switcher as well as the larger Ten Wheelers busy, leaving passenger service to #9 and the new arrival. She took over the daily Johnson City to Pineola run (Train 2/3) from #12 and spent a lot of 1926 on the regular run from Boone (Train 1/4) as well. She even spent time on the mixed train to Cranberry (Train 5/6), which was the only other passenger train on the schedule. For the first few years, #8 was a very busy engine. Most of the photos of #8 show her in passenger service or in the Johnson City shop area.

-H.W. Pontin photo, Railroad Photographic Service, Cy Crumley Collection.

-Photo, collection of Doug Walker.

-Photo, collection of Doug Walker.

ET&WNC #9 had the reputation of being a reliable and dependable engine year after year, but #8 turned out to be the exact opposite. Locomotive inspection reports beginning in June 1933 show the engine out of service for unspecified repairs, which lasted until early September. The Interstate Commerce Commission sent out inspectors to make sure that railroads were keeping their locomotives in good repair, and “the ICC Man” would always seem to show up on a bad day for #8. Every other month or so, the engine was out of service for light repairs during 1934. The engine was out of service the whole second half of 1935 for heavy repairs. Reports are missing for most of 1936 but it appears that the engine was in service much of that year. Number 8 was never painted green like the other Ten Wheelers or received the stretched lettering on the tender, as she had been freshened up with black in October 1935, a few months before the new scheme was created.

Number 8 came out of service in November 1936, but this time, instead of sitting on a siding at the shop, the engine was taken to Cranberry and set up in stationary service. The railroad had converted the drop pit in the no-longer-used engine house there to serve as a creosote dipping facility. The ET&WNC had used untreated ties throughout its history but wanted to try this new method of protecting wood. A line ran from the boiler down into the pit to provide steam to heat the gooey mixture. Number 8 was used in this capacity until August 1937.

After that the engine was again out of service at Johnson City, with the notation now saying, “not needed.” She sat out of service for nearly two years, until written off the company books on May 31, 1939. Usually this was the final document before an engine was scrapped, but the story was not quite over for #8. The shop crew removed the boiler from the running gear and set it back up at the Cranberry creosote facility. An extended stack was fabricated for the engine to aid the draft. This arrangement lasted until the facility was closed in December 1940. The boiler was then hauled back to Johnson City and installed in the back of the Johnson City engine house to provide heat for the huge structure. The remains of #8 were used for this purpose until finally being retired in 1947. The remaining narrow gauge equipment had been moved to Elizabethton in September 1946, when heavier rails were installed in the mainline and the narrow gauge third rail taken up. The last narrow gauge engine to arrive in Johnson City turned out to be final one in use there. A fitting conclusion to the story of a boomer locomotive.

This concludes my series on the narrow gauge engines of the ET&WNC. The Linville River Railway did own some narrow gauge geared locomotives, but they were covered in an article in the 2020 HOn3 Annual, published by White River Productions. A special thank you goes out to David Fletcher, who created the fabulous drawings that have accompanied this series.