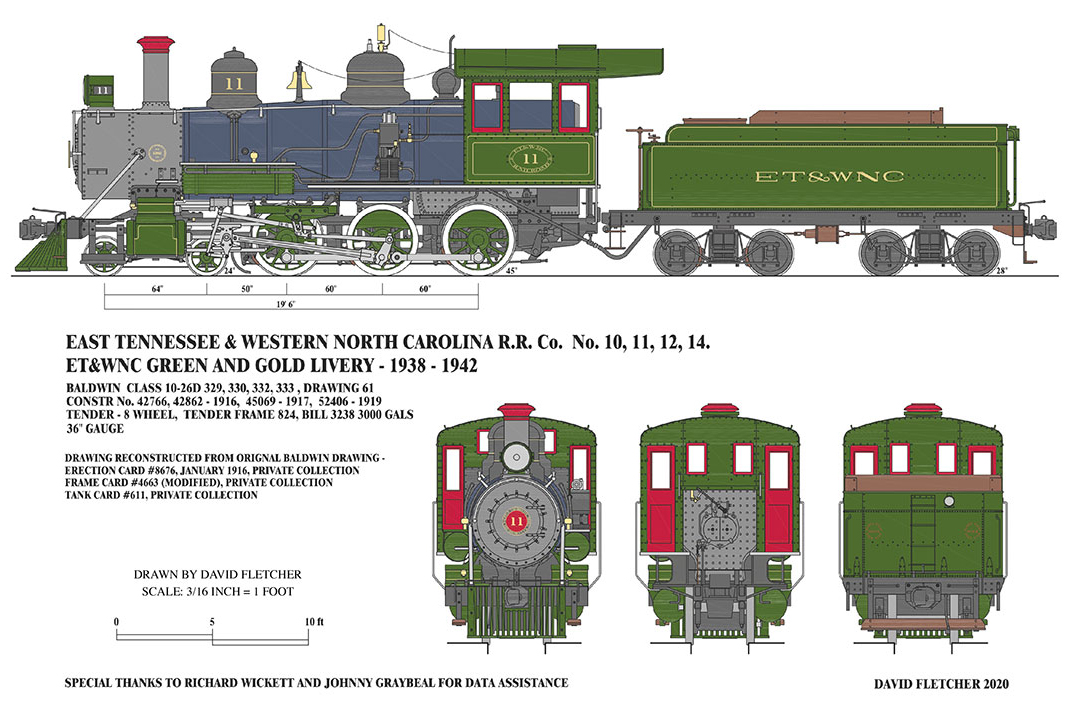

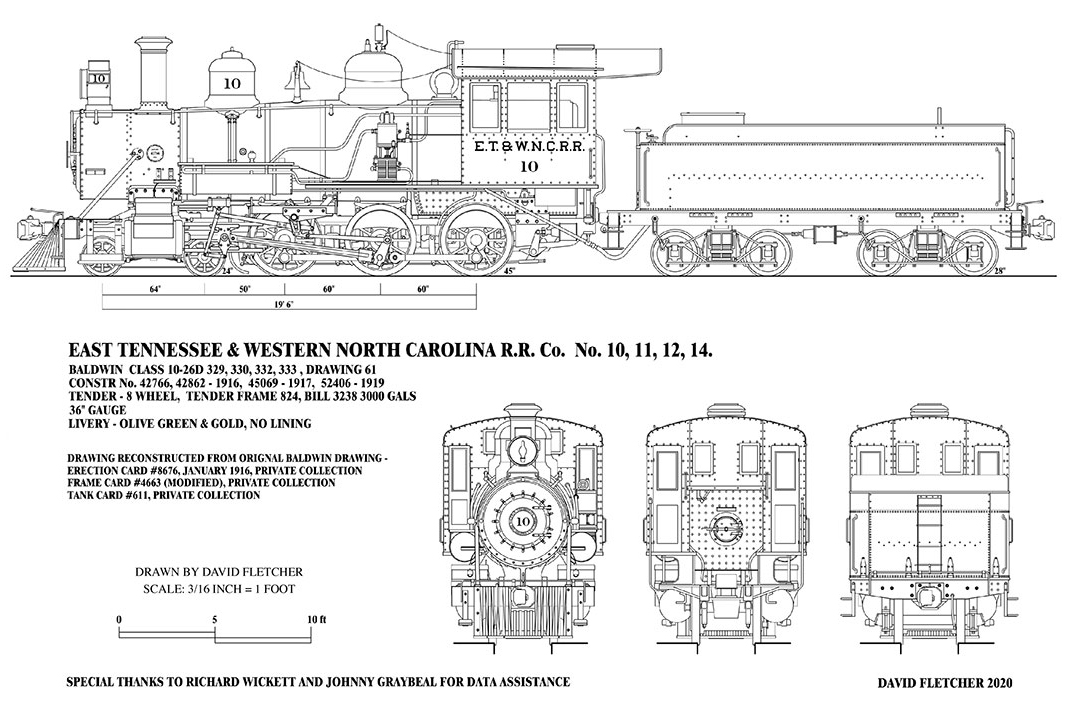

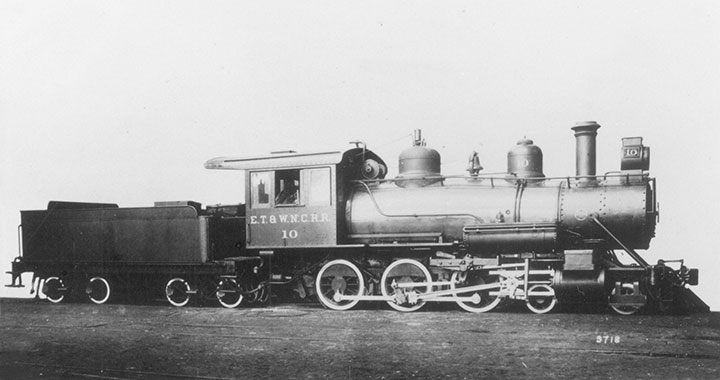

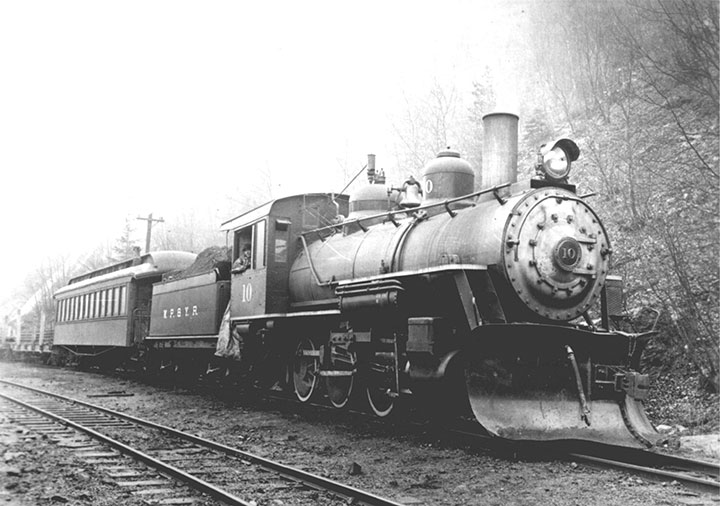

As I mentioned in the last issue, the management of the East Tennessee & Western North Carolina Railroad turned to Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1911 to design a locomotive for their specific needs. ET&WNC #9 was so successful that they went back to Baldwin in 1915 with a desire for an even larger engine. Baldwin responded with a scaled-up version of #9, that was a little longer, wider, and taller than the previous design. This design became drawing 61 of Baldwin Class 10-26D.

-H.L. Broadbelt Collection.

ET&WNC #10 had many modern features, but it retained the basic design traits that had defined most narrow gauge locomotives for 40 years. It used saturated steam running through slide valves to the cylinders rather than superheaters and piston valves currently in vogue on standard gauge lines. The Ten Wheeler design used a pony truck to help guide the engine into curves, but no trailing truck was used to increase the size of the firebox, meaning that #10 had a long, narrow firebox between the drivers. Forward and reverse was still controlled by a Johnson Bar instead of the new-fangled power reverse mechanism. Even with these limitations, it can be argued that the ET&WNC Ten Wheelers were the ultimate narrow gauge Ten Wheelers in American use. They certainly became that railroad’s trademark.

Engine Numbers 10 and 11 were ordered at the same time but built one month apart. Number 10 had a date of trial (first firing of the boiler) on January 5, 1916, and #11 was tested exactly one month later. They were delivered at a time of great expansion, with the Linville River Ry being extended to Shulls Mills, and a great deal of construction material was needed at the “front.” The new engines allowed the smaller Consolidations to concentrate on the construction trains while they handled the large quantities of iron ore being forwarded to Johnson City from the Cranberry mines, and the lumber flowing from the sawmills along the railroad.

The railroad to Shulls Mills was completed by the end of 1916, but there was still a need for more power on the railroad. A copy of #10 was ordered, and #12 was test fired on February 9, 1917. Identical in every way to the two earlier engines, #12 was still 2,800 lbs. heavier, bringing the total weight of the engine to 98,800 lbs., or near 50 tons. The increase could have been the result of heavier duty steel in the axles or frame, or lesser quality steel being used as the U.S. came closer to being dragged into WWI. One final example was ordered in 1919 and delivered in September. Number 14 was distinctive in that the boiler check valves were located on top of the boiler near the bell instead of down on the side of the boiler near the running boards. This allowed cold water to warm as it fell through the steam before hitting the rest of the water in the boiler, which in theory helped maintain boiler pressure. Number 14 also had a smaller diameter handrail on the front of the smokebox, making her easily identifiable in photos. Number 14 turned out to be the last new locomotive the ET&WNC purchased.

-Libby Watson Collection.

The story of these four locomotives is the story of the ET&WNC’s glory days and all of the years thereafter. They went to work during the busiest years of the railroad when the future looked extremely bright. For the first few years, revenues increased with each passing year. Passenger income peaked in early 1924, when over 205,000 people rode the narrow gauge rails, bringing in $74,741 in the fiscal year ending June 30, 1924. Freight tonnage was just as impressive, with figures totaling over 325,627 tons in fiscal 1923. Some of this was standard gauge traffic but it was all pulled by narrow gauge motive power. It was rumored that Henry Ford was going to buy the ET&WNC because it was so profitable. Of course, the rumors weren’t true, but it made good press.

The Ten Wheelers were the railroad’s main motive power and ended up in their share of derailments and accidents. Number 10 derailed shortly after she was delivered on light rail at Newland, North Carolina. She later ran too far up onto a tipple there and almost fell through it. The worst accident of all occurred on March 5, 1925, in Johnson City. Number 12 had just returned from the passenger run to Pineola and was headed to the engine house. The fireman and another employee were waving to the lovely wife of the fireman when they hit some boxcars being moved in the yard by the switcher. Number 12 was heavily damaged, essentially destroying the smokebox and causing damage to the frame. The brass number plate was almost completely broken in two, but Andy Kern was able to heat it and get it back together. The shop crew rushed repairs and the engine was back in service in only two weeks. Crews said she rode rough after the accident and was not a popular engine with them. The issues with the frame were not completely repaired until a full overhaul was performed in 1999, nearly 75 years later.

Unfortunately, the ET&WNC’s future was not as bright as everyone had expected. The automobile and newly constructed roads took a hefty bite out of passenger revenues. After the 1924 peak, numbers dropped off drastically with each passing year. The railroad continued to do well financially due to the construction of rayon plants along the dual gauge section in Elizabethton, Tennessee, in 1926. This brought a great deal of standard gauge business to the railroad. The fire hazard at these plants was so high that the Ten Wheelers lost their trademark capped stacks in favor of a straight stack with a flip up spark arrestor. The plants purchased their own standard gauge fireless switcher from Porter in 1935, allowing the engines to return to their normal configuration.

-Wayne Arnold Collection.

As more roads were built in the mountains, the passenger business continued to decline. In 1932, the railroad began running excursion trains to bring in tourist dollars. The ET&WNC/LR system had some beautiful scenery along the tracks, some of it completely isolated from any roads. Throughout the 1930’s excursion trains ran every other Sunday from June into October. These trains were four cars long and were usually packed, while the daily except Sunday Mixed train usually carried less than 12 people. It was during the Great Depression that the ET&WNC acquired a nickname... “the Tweetsie.” A coach at Appalachian State Teachers College coined the phrase, and by 1937 the word had become common usage. The name was not applied to any one locomotive but to the railroad as a whole. A Universal Film short, titled Tennessee Tweetsie appeared in theaters in 1939, and a legend was born.

-Mike Dowdy Collection.

-Ken Marsh Collection.

The Great Depression was gradually coming to an end when a major hurricane hit the area in August 1940 and washed out the Linville River Railway. That part of the system had not made money in several years so permission from the ICC to abandon it was received in 1941. The narrow gauge section of the ET&WNC was now a very unprofitable branch, supported by the standard gauge business between Johnson City and Elizabethton. The retirement of Switcher #7 in 1938 had brought standard gauge engines to the railroad, so more room was needed in the engine house. The railroad started major overhauls of the Ten Wheelers, with #14 passing through the shop in 1941 and #10 in late 1941 and early 1942. Once all four of the larger engines were shopped, the plan was to retire #9.

WWII intervened. In May 1942, the U.S. War Department wanted to purchase the two best engines for the war effort. Numbers 10 and 14 left that month, headed for far off Alaska for service on the White Pass & Yukon Route. Once in the great white north, the engines received some modifications to their running boards and were put into service as switchers, one in Skagway and the other in Whitehorse, Yukon Territory. In the spring of 1943, they were shipped back to Tacoma, Washinton, for major modifications. They came out of the shop with their cabs set back about one foot, making them open cabs; insulated smoke boxes, snowplow pilots, and other small changes. They returned to the Yukon and were both assigned as switchers in Whitehorse. They were in the engine house on Christmas Day, 1943, when fire gutted the facility. Both engines were irreparable and were eventually sent back south in 1946 for scrapping.

-Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, Museum of History & Industry, Seattle Washington.

-Railroads in Alaska & Yukon Collection, Univ. of Alaska, Anchorage, AK HMC-0265.

Numbers 11 and 12 served throughout WWII on the ET&WNC with #9, pulling the commuter trains that served the rayon plants three shifts per day, seven days a week. Two of the engines were necessary to cover these commuter runs, leaving only one to cover freight trains. One fireman was quoted as saying that “he worked nine days and nights without ever taking his shoes off.” His sleep came in the cab between runs. Near the end of the war, both locomotives had their original cowcatchers replaced with smaller ones made from boiler flue tubes.

-D. B. Marion Photo.

-William T. Miller Collection.

Just before the war ended the commuter trains stopped running and business dropped off sharply on the narrow gauge. In the summer of 1946, the segment between Johnson City and the rayon plants received 112 lb. replacement rails. Rather than replace all three rails, the narrow-gauge equipment was moved to a newly constructed yard just east of downtown Elizabethton. For the next four years the narrow gauge ran on borrowed time while the railroad generated the documentation to justify abandonment. Number 12 did not run after October 1949 and sat in a newly constructed engine shed in the yard, while #11 pulled the dwindling freight tonnage.

The last run of the narrow gauge ET&WNC came on October 16, 1950, when #11 made one more run to Cranberry and back to Elizabethton. Number 11 was cut up for scrap in 1951, but the story was not yet over for #12. She sat in the shed while not one, but two groups worked to purchase her for an operating narrow gauge museum. Three railfans succeeded in buying the engine and two cars in December 1952 to form the Shenandoah Central tourist line. With this equipment and a coach from the East Broad Top, they operated for two summers, carrying tourists on a one mile stretch of track near Harrisonburg, Virginia. Hurricane Hazel damaged this line in October 1954 and the equipment was again put up for sale. Cowboy legend Gene Autry had an option to purchase, but ultimately sold the train to Grover Robbins Jr., who brought it back to North Carolina to form the Tweetsie Railroad in 1957. At 104 years old, now Tweetsie Railroad #12 is still running up four percent grades and around steep curves as she carries smiling tourists on Wild West adventures. A fitting end to a very successful story of this class of locomotives.

-Caleb Reeves Collection.

-Caleb Reeves Collection.

-Curtis Brookshire Photo.

The 10-26D Class was the ultimate development of the Ten Wheeler on American narrow gauges. Ten Wheelers were usually built for speed, something rarely needed on spindly narrow gauge lines. The ET&WNC found them to be perfect for their needs, and never seriously considered larger power. That one of them has not only survived, but thrived for over 100 years is a testimony to that achievement. Number 12 at Tweetsie Railroad is a fine testimony to narrow gauge railroading in the southeastern United States, and deserves its place in narrow gauge fandom.

This class of Ten Wheeler has the distinction of being produced in three model railroad scales. Bachmann Industries first offered its Bachmann Big Hauler in 1988, using measurements of #12 provided to them. It was offered in ET&WNC lettering in 1994. An On30 version was released by Bachmann in 2009. Train & Trooper imported a run of brass engines in 2009, faithfully recreating engine details and four distinct paint/lettering schemes.

Number 14 may have been the last new locomotive purchased by the ET&WNC, but the story of their locomotive roster does not stop here. There were a couple of used engines purchased over the years, and their story will be told in future issues of the GAZETTE.