It is no coincidence that the White Pass & Yukon Route’s slogan is “The Scenic Railway of the World.” If you have managed to visit the WP&YR, you understand that slogan. The history as told by the locomotives of the White Pass is just as spectacular. Part 1 was in the March/April issue and covered the history of the White Pass locomotives numbers 1/51 and 2/52: the first locomotives in Alaska. Here in Part 2, I will cover the history of the White Pass number 3/53, another early locomotive of the line and its D&RG connection.

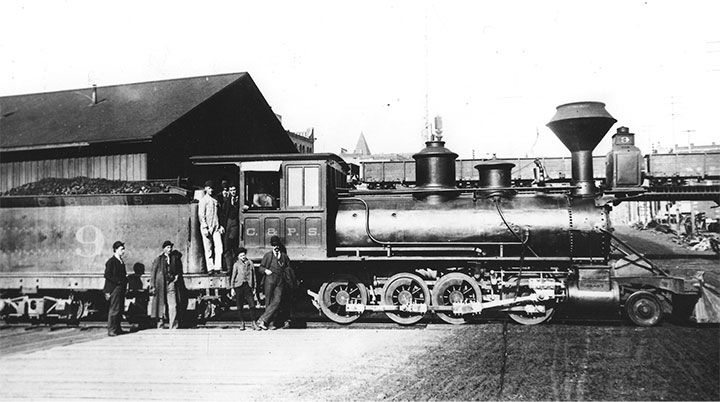

-Photo, collection of David Fletcher.

White Pass number 3/53 was built by Grant Locomotive Works of Paterson, New Jersey, in 1882, most likely in February. It was part of a large order of 2-8-0, Class 60 locomotives placed by the Denver & Rio Grande (D&RG) in 1881, from both Grant and Baldwin Locomotive Works. (For more info on the D&RG Class 60 engines, see the seven-part series by Mallory Hope Ferrell starting with the May/June 2004 GAZETTE). Grant delivered 30 of the 40 engines ordered in 1881, but the financial arena had changed by the end of the year for the D&RG. Grant apparently completed these last ten Class 60 locomotives in February of 1882, but the D&RG did not have the money to pay for them and therefore refused them. The D&RG claimed that the refusal was because the locomotives were not delivered within the contract time, yet the railroad had already refused the last two of the first 30. There was not an immediate buyer, so it appears that Grant “sat” on them until June of that year when the Toledo, Cincinnati & St. Louis RR (TC&StL) bought the ten engines.

The Toledo, Cincinnati & St. Louis RR was a 3-foot gauge railroad in western Ohio. This railroad started in the 1870s and grew by numerous mergers and agreements. The TC&StL entered in an agreement with the Ironton RR (later the Dayton & Ironton) allowing narrow gauge rails to be laid between the Ironton RR’s rails. In 1882, the TC&StL merged with the Toledo, Delphos, and Burlington Railroad keeping the TC&StL name. The TC&StL acquired the 10 Grant-built locomotives in June of 1882, and most likely numbered the ten engines in sequence according to construction number as this seems to have been their practice. Our subject locomotive became TC&StL #63. Because of this numbering practice, it is believed that the TC&StL #63 was Grant shop #1451. Furthermore, based on this, it is conjectured that the D&RG road number was to have been #236. The contract of June 1882 between Grant and the TC&StL originally appeared to have been a lease, but the courts later deemed it a contract of purchase.

The year 1883 saw the TC&StL absorb the Cincinnati Northern Railway (CN) in May and #63 was either sold or transferred to the CN where it retained the number 63. By July of 1883, the TC&StL was in a sad state; less than a third of the line was ballasted, trestles were not safe for the trains, and the employees hadn’t been paid since May. A receiver was appointed in August and the Grant Locomotive Works demanded the return of #63 and nineteen other locomotives. The receiver made a couple of counter offers to Grant, one of which Grant accepted. The locomotive would stay on the Cincinnati-Dayton portion of the line for now with a lien placed on the property for the balance due for #63 and one other locomotive. The TC&StL was split at foreclosure in June of 1884, and the Dayton & Ironton RR was formed. The CN was sold in June of 1885, while still in receivership to its bondholders who incorporated it as the Cincinnati, Lebanon & Northern Railway (CL&N) in July. Number 63 was transferred to the new CL&N, again retaining its number, but was not likely used by the CL&N because according to The Nickel Plate Story by John A. Rehor, most of the Grant “engines were laid up with broken frames, burned-out fireboxes, and boilers full of mud” by 1885. Exactly what was meant by these expressions is hard to say, but we can speculate from the poor financial track record of the TC&StL that there was most assuredly a lack of proper maintenance on the locomotives leading to their poor condition. Furthermore, it doesn’t appear #63 ever left the Dayton & Ironton portion and by April of 1887, was listed as “laid up” in Dayton, Ohio. This was the same month that the D&I RR was converted to standard gauge and Grant repossessed the locomotive from the CL&N as the D&I never owned the engine.

Grant managed to resell #63 to the Oregon Improvement Company on September 30, 1887, but the proceeds fell short of what was owed, and the CL&N had to pay Grant the difference. The Oregon Improvement Company (OIC) had purchased the Seattle & Walla Walla Railroad and Transportation Co. in 1880 and renamed it the Columbia & Puget Sound RR (C&PSRR). The OIC was a subsidiary of the Northern Pacific and improvements were made during the mid- and late-1880s. This is when the C&PSRR acquired the ex-TC&StL #63 from Grant and she became the C&PSRR #9 in Washington State. The narrow gauge Columbia & Puget Sound was standard gauged ten years later in 1897, and the locomotive was due to change hands again.

Construction of the White Pass & Yukon Route began on May 28, 1898, in Skagway, Alaska. The builders were looking to cash in on the swarms of Klondikers headed for the gold fields of the far north. The first railway in Alaska was looking for motive power; lots of motive power. The WP&YR found a handful of locomotives available for sale relatively nearby from the recently standard-gauged C&PS. Our subject most likely arrived in Skagway in late July or August of 1898 lettered for the WP&YR #3 and was soon hauling construction trains up the 3.9 percent grades out of Skagway. In February of 1899, #3 had the distinction of pulling the first passenger train to the White Pass summit twenty miles from Skagway. The locomotive had changed little from what is thought it looked like when built, but the sand dome had been moved forward slightly and the bell was now between the domes. Whether these changes occurred on the C&PS, or when it first arrived in Skagway is simply not known. The White Pass rebuilt the #3 in 1899 or 1900 with an extended smokebox, straight stack, a new headlight, and moved the bell to a position between the cab and the steam dome. The locomotive was renumbered from 3 to 53 in 1900, and labored on the White Pass until 1907, when she was listed as retired. This ended a twenty-five-year career in two states, one U.S. territory, and two countries. Number 53 was finally scrapped in Seattle, Washington, in 1918.

-Photo, Case & Draper, collection of Bruce Pryor.

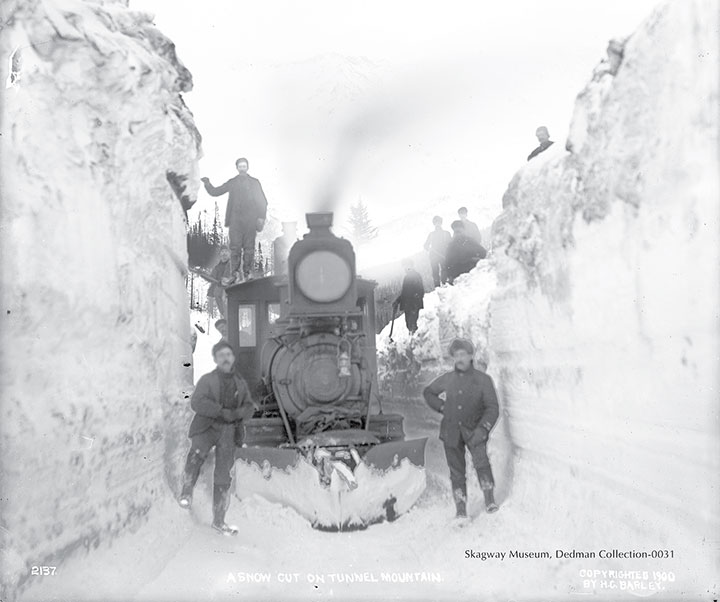

-Photo, Skagway Museum Dedman Collection-0031, high resolution scan by Chuck Morse.

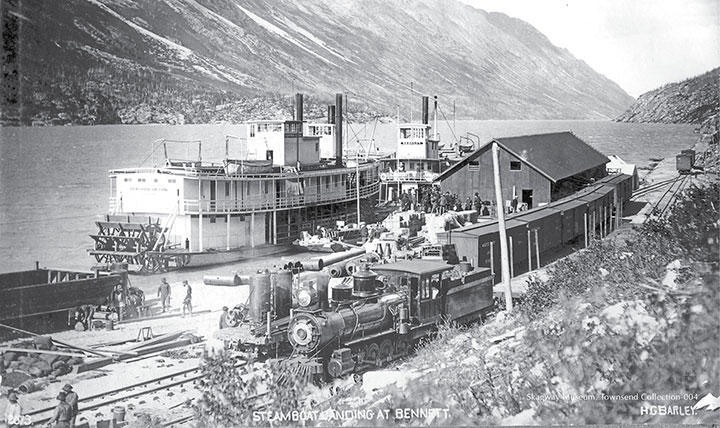

-Photo, H.C. Barley, collection of Bruce Pryor.

-Photo, H.C. Barley, Skagway Museum Townsend Collection-004, high resolution scan by Chuck Morse.

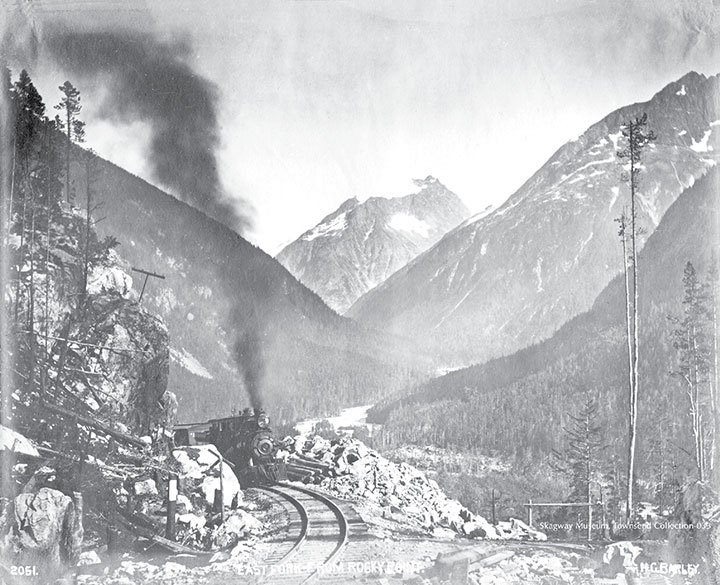

-Photo, H.C. Barley, Skagway Museum Townsend Collection-033, high resolution scan by Chuck Morse.

-Photo, Case & Draper, collection of Bruce Pryor.

It has been speculated that #53 was probably quite slippery on the generally wet White Pass rail conditions of southeast Alaska, which are very different conditions from western Ohio or the Rocky Mountains of Colorado. The year 1907 also saw the delivery of the largest 2-8-0 built up to that time, WP&YR #68, and that locomotive will be a subject of a future article here. Suffice it to say that #68 could handle roughly twice what #53 could. Another factor for the 53’s retirement may have been the Interstate Commerce Commission’s prohibition of wrought iron boilers in interstate service that went into effect around 1908, (crossing the Canadian border would have been considered interstate commerce).

This locomotive had a very sorted history; refused by the railroad that had commissioned its construction, sold instead to a railroad that was for all intents a financial “train wreck,” repossessed by its builder, and sold to a railroad in Washington state only to be resold a few years later to the White Pass & Yukon Route in Alaska. Number 3/53 was the only “D&RG connection” for the White Pass until World War II. Number 3/53 wasn’t on the White Pass nearly as long as the first two engines, but she outlasted others that shared the rails with her in Washington and Alaska.

I would again like to thank Boerries Burkhardt, Robert Hilton, Chuck Morse, Bruce Pryor, and John Stutz for their assistance and generosity with photos and information. Also, a huge thank you to David Fletcher for another set of his magnificent drawings. In the next issue, I will investigate not one, but two locomotives that plied the rails of “The Scenic Railway of the World” with more beautiful drawings by David Fletcher.