A lot of the kits I build do double duty. Besides finding them of interest and hopefully, of future use on my decades-long planned layout, they usually are review items for the GAZETTE. Such projects are doubly satisfying in serving both purposes and explain why modifications are sometimes made or extra details are added. But occasionally between deadlines, I get to build projects just for me and just for the fun of it. Recently, I converted two junked train show vehicles into cement trucks by marrying their truck chassis to toy cement truck drums, obtained years before at a 5 and 10 store. (Remember those?) Other times I have repaired or modified train show bargain rolling stock, as described in past columns in the GAZETTE.

My friend, Kevin Feeney, haunts Train Shows primarily on the East Coast. A seasoned traveler and expert on using bonus miles to score airline tickets, he will happily jet off to a weekend train show just to wander the aisles for the bargains to be found. When he comes across something of potential interest, he will shoot me a cell phone photo asking if I am interested. He jokingly refers to himself as my “personal shopper!” Not really a joke as he has found any number of great finds. On one occasion, he found two rare very early kits for American rolling stock but made in Japan. No, not of brass, but like the craft kits of the early to mid 1950s with wood and stamped lithographed metal components. What set these cars apart from their American contemporaries was the method of assembly. Both utilized a cleverly engineered and mostly “mechanical” method of assembly. By that I mean the use of nails, screws, tabs, and slots to attach the disparate parts to each other with little or no glue used.

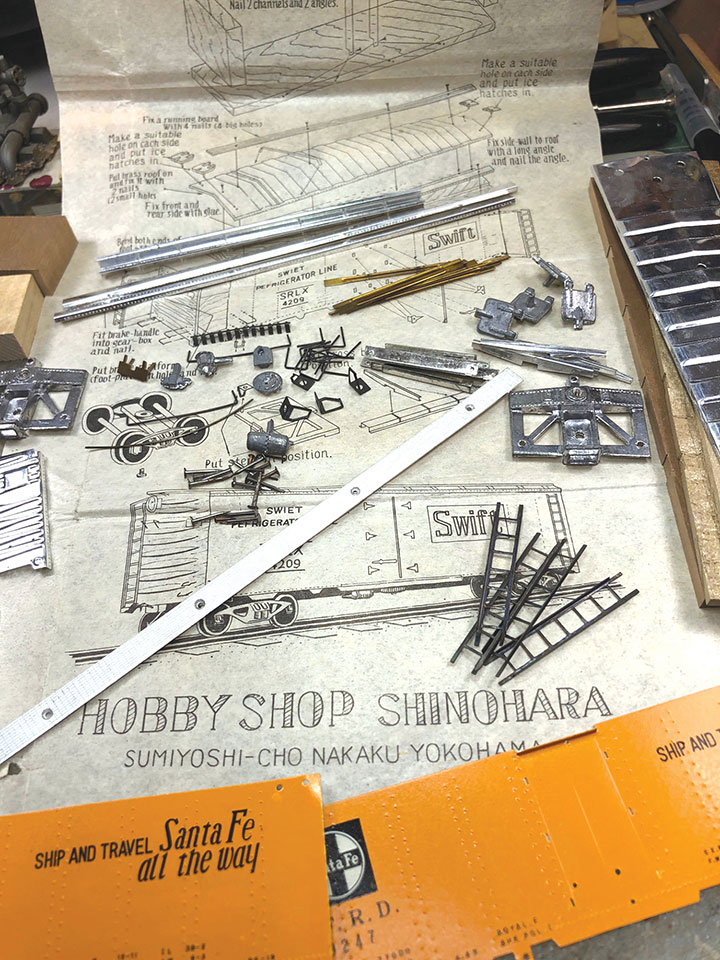

The kits were a Katy 40-foot steel sheathed boxcar from a company called the “New One Model Toy Works Ltd. in Tokyo, and an ATSF SFRD steel-sided reefer from “Hobby Shop Shinohara” in Yokohama. These Japanese kits were different from each other and from American kits in some ways while similar in others. Both contained beautiful, lithographed metal sides with rivet detail, albeit oversized. The New One kit was almost entirely metal, complete with shiny components and a bag of miscellaneous parts. Trucks and very strange couplers were included. The one-page instruction sheet was amply illustrated with minimal English instructions showing each step. The Shinohara kit was a combination of wood shapes with lithographed metal sides and stamped ends. No couplers or trucks were included though trucks were pictured. It reminded me more of the traditional kits of the early 1950s except that the fine-grained wood appeared to be a mahogany or teak. An onion-skin paper illustrated instruction sheet covered the basics of assembly.

Before I built the kits, I wanted to learn more about them and thus contacted my friend, Kenichi Matsumoto, in Tokyo. Kenichi, former editor of Train, Japan’s leading model railroad magazine, is a fount of knowledge on Japanese products and his reply did not disappoint.

According to Kenichi, New One Models was established by Mr. Shin-Ichi Ikuma. The first name, “Shin” means “New” and “Ichi” means “One.” So, Ikuma used them to create his company’s name. As soon as the Pacific War ended, many American GIs were stationed in Japan (including my father) as part of the Occupation force, and hobby shops were started or restarted to serve these GI modelers. Kawai Models and Tetsudo Mokeisya were among the first group in Tokyo. Shinohara Hobbies and Toby established operations in nearby Yokohama. Shinohara Hobbies, whom I assume later made track, started with a small booth in the Post Exchange (PX) of a U.S. military base there.

Tenshodo was rather a late comer among them. Tenshodo was, and is, a jewelry store on the Ginza in Tokyo. Because jewelry was not in demand in post war-torn Tokyo, the model division of Tenshodo started its business in June 1949, the same month and year as Kenichi was born and a year after I was born, also in Japan ironically. At its beginning, Tenshodo did not have its own workshop or factory. They mostly utilized craftsmen who had been amateur modelers before the war, and under contract, created small quantities of hand-made products for Tenshodo to sell.

Following WWII, “New One Models” became the first model builders in Japan with a commercial base production using die-casting, printed cardboard, pressed tinplate, and machine-milled woods. Kenichi surmises that New One obtained some of the U.S.-made freight car craft kits from the GI modelers and designed their products by copying those U.S.-made kits in part. At the beginning of Tenshodo’s model division, New One became their main supplier. They kept this partnership throughout the 1950s.

In May 1952, for Kenichi’s third birthday, his father gave him his first HO train set which he bought at Tenshodo’s shop on the Ginza in Tokyo. It contained an 0-6-0 tank engine, two freight cars and a red caboose. All of them were New One products. New One also supplied products to the shops near U.S. military bases and offices. In Tachikawa, my birthplace, New One supplied the Nozawa Instrument Shop which later became “Takara,” a supplier in the brass model world.

Among Tokyo’s hobby outlets, one, located in the large office building just in front of the Tokyo Train Station and near General MacArthur’s headquarters (where my father worked), was a branch of a famous stationer’s shop named “Haibara.” While Kenichi did not know the reason, they also became a showcase for New One’s trains. Because Kenichi grew up on the opposite side of the station, visits to that shop are a fond memory from his youth.

Many GI modelers also brought back New One’s products to the United States when they returned from service. Kenichi surmises my two cars might be a part of that story.

In the late 1950s, the New One company dissolved their relationship with Tenshodo, switching their business partner to Aristo-Craft in the U.S. Aristo-Craft was started by Nat and Irwin Polk who owned Polk’s Hobby Shop in New York City. Polk’s Hobby Shop advertised for years in major American model railroad magazines selling their line of products nationwide. For Aristo-Craft, New One made several low-priced HO die-cast steam locomotives. By the early 1960s, Polk’s was importing European and Japanese models under the Aristo-Craft banner. The New One line of die-cast locomotives, beautifully packaged in bright lithographed boxes, became an alternative to the brass imports of the era and included many unusual and old-time prototypes. They had a 2-4-2 and an 4-2-2 for example. I have a complete set of these engines and recall obtaining my first one in about 1962. I often wondered who “New One” was; now, thanks to Kenichi, I know.

Apparently, New One turned from the model train business to making home movie projectors and retired from the model train business rather abruptly and completely. This may explain why the last advertised locomotive from Aristo-Craft, an 0-4-4T Mason, never appeared. This is the story Kenichi provided concerning the New One Company and to a lesser extent, Shinohara Hobby’s kit activities. A full article by me on New One and the Aristo-Craft locomotives will appear in a future issue of HO Collector magazine. Shinohara Hobbies must have turned to track manufacturing at some point. I assume that the freight car kits were produced by them for sale in their shop in Yokohama. It is also possible the reefer kit made the trip to the U.S. with a returning GI.

I tackled the New One boxcar kit first. It was so different building an HO car using tabs and screws, not glue. An L bar with tabs fit atop the lithographed sides which tabs were bent to fit into slots in the sub-roof. This secured the sub-roof to the sides, creating part of the complex roof profile. Staple-style grabs were inserted, and the ends bent inside to secure them. Then, corner steps were riveted on from beneath into the metal floor. All holes were pre-drilled. The rudimentary brake gear details were inserted into holes in the floor and a small hammer used to flatten their pins from within. Roof ribs of formed brass were next bent over the metal roof and crimped in place. Next, the roof was screwed from underneath, fastened by the roof walk to the body. The floor was then screwed from beneath to tabs bent from the sides. (I added weights to the inside floor). The ends were slipped into the roof and over the sides, screwed by tabs, to the floor. All pieces thus interlocked. The couplers (I substituted Kadees) and trucks were finally screwed to the floor. The kit trucks were out of gauge, so I substituted another pair. Even the brake wheel and housing were attached to the end wall by a tiny nail driven into a provided small block of wood behind the end wall to secure them. The kit is a marvel of primitive HO engineering. Though certainly crude by today’s standards, the result was an acceptable and charming boxcar. I painted the roof, doors and ends black.

The Shinohara kit was less impressive engineering-wise, but still ingenious. Although using a wood block sub-structure like then-contemporary American kits, the car was designed to be nailed together with two sizes of nails, not glued as most contemporary American-made kits. I substituted ACC mostly but did nail a few pieces for strength. I must admit that nailing such tiny nails while not pounding the whole car to pieces would be a challenge. The wooden floor and roof sides were pre-marked for spacer bars to be inserted and “nailed” in place. I elected to use superglue. The bottom channel and side sills were metal shapes also notched and pre-marked to ease assembly. Grabs, door hinges, latches and steps were inserted, and tabs bent to secure in place. I had to fudge on the door latches as the supplied ones were too short. Like the New One kit, the metal roof and ends interlocked with the sides to create a uniform appearance. Although pictured in the instructions, my kit contained no trucks, as I earlier noted. So, I added a pair from my collection plus Kadee couplers. The result was another attractive and acceptably detailed car.

If you question the connection between this topic and the “Narrow Gauge Scene,” I admit it is a stretch. But it is interesting to learn of the antecedents of many of the suppliers of narrow gauge brass trains and track. So that is my rationalization. Also, there is great fun in assembling vintage kits requiring skills that often are vastly different from those required today. These kits were manufactured to be built, not sit in a box. And since these two cars appeared, Kevin found yet another early kit from Japan: this one, an old-time coach. Maybe another time I’ll build it, but that’s all for now. Until the next time—write if the mood strikes.