The East Tennessee & Western North Carolina Railroad had barely survived its first twenty years of operation. Unhealthy business decisions by her parent company Cranberry Iron & Coal, and poor business conditions in the South in the last two decades of the 19th Century had strained the railroad almost to the breaking point. A disastrous flood in May, 1901, would have ended the story of this little narrow gauge line had a few smart investors not made some changes that would turn the whole situation around. Instead of dying, the railroad gained new life and entered a period of great prosperity.

One casualty of the flood was Railroad Superintendent C.H. Nimson. He was replaced by George Hardin, a Johnson City local, and relative of one of the founders of the railroad. Hardin was a very able manager and was soon promoted to Vice President and General Manager. The railroad was now a conveyor belt for iron ore to the furnace at Johnson City, so money was available to repair and improve the line. The washouts from the flood were replaced with stone and concrete retaining walls that have stood the test of time for over a century. Wooden bridges were replaced with steel. With plenty of tailings from the mine to use for crushed ballast, the ET&WNC quickly became as stable as any of the standard gauge lines in the region, able to haul increasing business to the outside world.

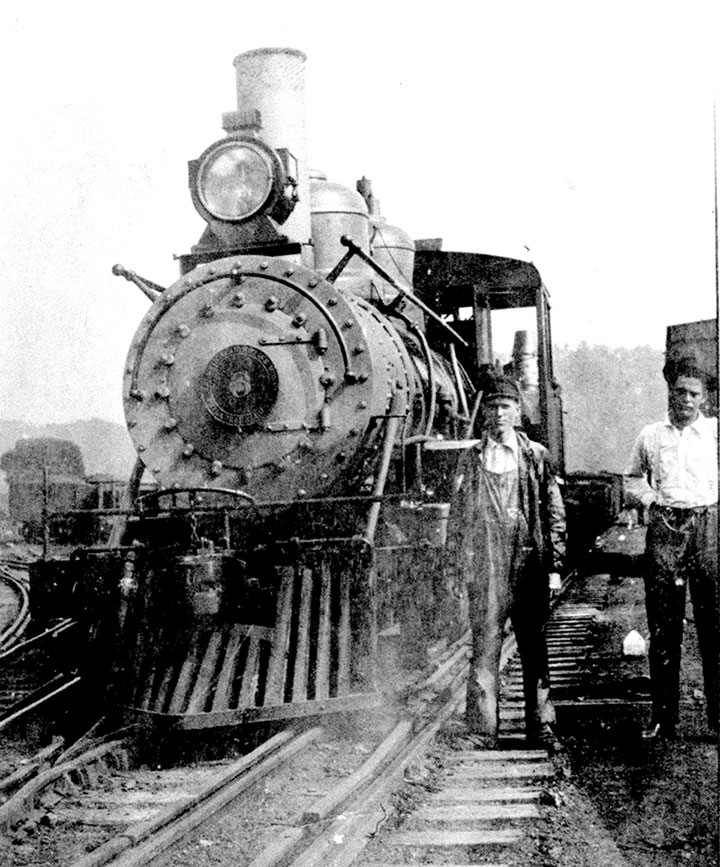

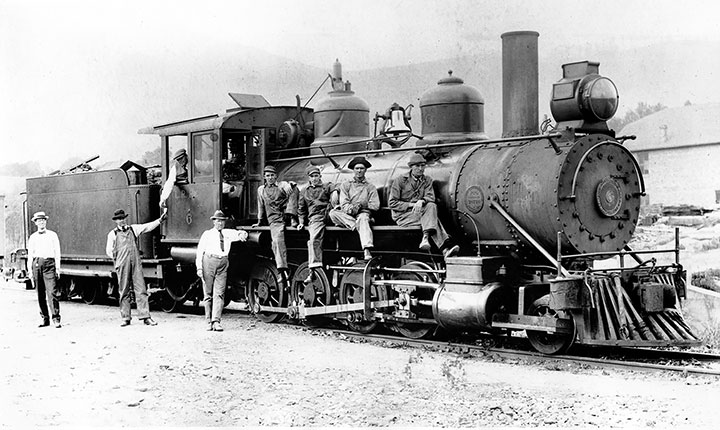

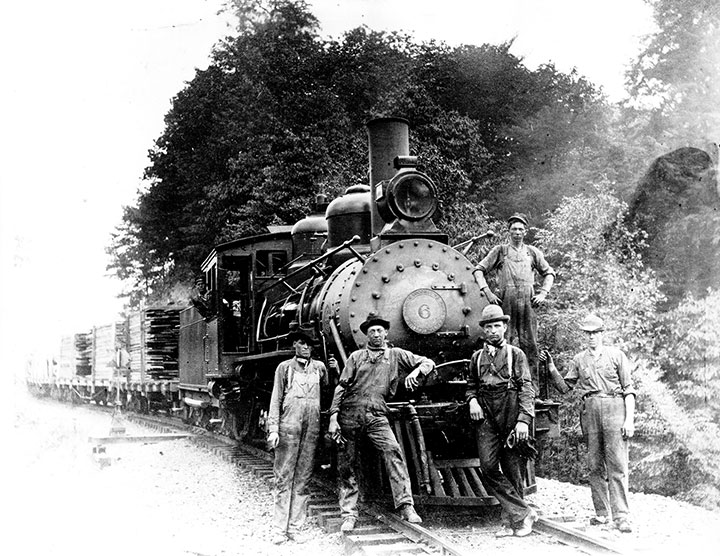

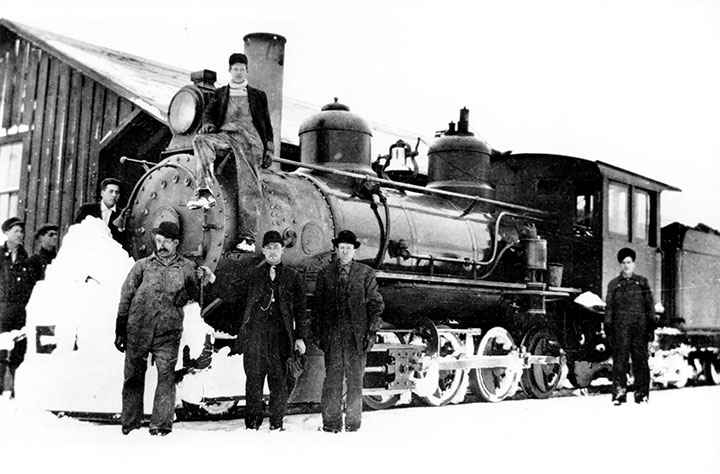

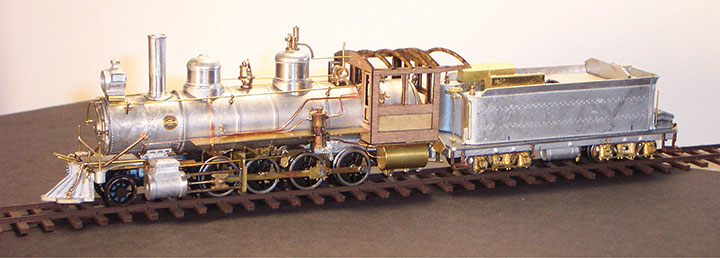

To handle this increased tonnage the railroad needed more motive power. The locomotives from the 1880s were now 20 years old and near the end of their useful lives. Hardin turned to Baldwin Locomotive Works to produce proven drawings of Baldwin Class 10-26E for the three new locomotives. Number 4 was a copy of the Florence & Cripple Creek 2-8-0s, as well as two Silverton Northern locomotives. Delivered in November, 1902, and January, 1903, numbers 4 and 5 took over the freight hauling on the now busy narrow gauge. In October, 1904, #6 was delivered. Visually identical to the previous two, #6 had thicker stay bolts and a slightly thicker boiler, both necessary to provide an increase of boiler pressure from 160 lbs. for #5, to 180 lbs. for #6. This change made #6 more powerful, but not larger than the earlier locomotives.

These three locomotives powered the freight trains through the first decade and a half of the 20th century, years of continuous growth. In 1904, the management decided to put in a standard gauge third rail between Johnson City and Elizabethton to take advantage of a demand for cheaper coal from southwest Virginia. Rather than buy standard gauge locomotives, the narrow gauge freight locomotives had unique swivel couplers installed that allowed them to move cars of both gauges.

The Linville River Railway (LR) was constructed in 1899 to provide rail service for a W.M. Ritter bandsaw mill going up at Pineola, North Carolina, twelve miles from Cranberry. This provided the ET&WNC with a lot of bridge traffic, hauling cut lumber to the outside world. Other lumber operations at Hampton and Elk Park gave the freight locomotives plenty to pull. The iron ore business grew as well, and the railroad built two bay wooden hopper cars to haul ore directly to the furnace. Passenger business grew to the point that the management elected to buy a dedicated passenger locomotive. With so much business of both gauges in Elizabethton and Johnson City, a dedicated switcher was purchased to keep freight moving.

The second decade of the century was just as busy, if not more so. The first mixed service Ten Wheeler, #9, was purchased in 1911, but she was used on the Cranberry Local, a mixed passenger and freight train that hurried passengers and fast freight out of the mountains each morning. It would be another five years before more locomotives were purchased, so the Consolidations continued to move most of the freight. They also powered Sunday School specials, long trains with every passenger car on the roster filled with sightseers, the predecessors of the excursion trains that plied the rails decades later.

That logging road feeder line, the Linville River Railway, waxed and waned as Ritter cut his timber and then moved out, leaving the mill for another company to use to cut the hardwoods that Ritter had left. Other logging companies sprang up along the LR, but by 1913, most of the timber had been harvested. It surprised everyone when the LR was purchased by Cranberry Iron & Coal, making the LR a sister company to the ET&WNC. The LR only owned a Shay locomotive at the time of the purchase, so once the track was improved, the ET&WNC sold them Consolidation #4 on June 30, 1915. By that time #4 was the oldest locomotive on the property.

During these years of steady service, the locomotives were involved in accidents on a regular basis. Numbers 5 and 6 met head on between Elk Park and Shell Creek on the 4 percent State Line Hill grade. The pilot of one of the locomotives was damaged, which left it vulnerable to a fallen rock the next day, damaging her cylinders. According to the old timers, #4 was never the same afterward. On another occasion, #5 ran through a split switch and completely turned over. These accidents and others caused numbers 5 and 6 to get steel cabs to replace damaged wooden cabs. The addition of handrails and modified smoke box fronts gave them each a more modern appearance.

One thing about the lumber business in those days was that there was always another stand of timber just a few miles away, waiting for the company who could get rail service. In November, 1915, an extension was begun from Montezuma, near Pineola, running off to the northwest toward Watauga County and a large stand of virgin timber. William S. Whiting offered a bond reward if the railroad was completed to his bandsaw mill location at Shulls Mills by September 30, 1916. Numbers 4 and 5 were used extensively on this extension, being able to more easily negotiate the newly laid tracks.

With narrow gauge tracks ranging further and further from Johnson City, the ET&WNC decided to buy even more motive power. Ten Wheelers numbers 10 and 11 were built in January and February, 1916, freeing up the two Consolidations to haul material to the advancing front. After the line to Shulls Mills was completed, #6 was sold to the Linville River in October, 1917, and #5 followed in December, 1919, after the line to Boone was completed. By that point, all of the smaller locomotives were serving on the LR.

While these locomotives spent most of their time on the Linville River side of the system, they did find their way back west quite often. The Consolidations helped power the short lived Jitney commuter trains of 1924, extra passenger trains on the weekends, and forwarded freight trains on to Johnson City from Cranberry. The two railroads kept up with the comings and goings, with funds exchanged when one line used another’s locomotive.

What is forgotten today, is that these three locomotives soldiered in relative obscurity throughout their lives. Like most narrow gauge lines, there is a period between the professional photographer taking glass plate negative images in the 1800s and the railroad enthusiasts’ Kodak images from the Great Depression. Except for a few real photo postcards done in the Teens, the ET&WNC Consolidations ran along day after day with few to record their passing. Even those images concentrate on the crew, those dashing young men who ran trains in those days. The locomotive is just the backdrop, like the 18-wheeler would be two generations later.

The service of the Consolidations was tied to the fortunes of the company. The Whiting mill closed permanently in late 1925, with the equipment moved out in 1928. All Linville River train mileage up to 1925 had been mixed train miles, hauling lumber out of Shulls Mills and general freight to Boone. As the number of trains declined, the larger Ten Wheelers of the ET&WNC took over moving the business that remained. Number 5 came out of service on April 28, 1928, for flue renewal. The job was begun but never finished. She sat in the Johnson City yard with the smoke box front removed for eight years, until she was officially retired on June 23, 1936. Numbers 4 and 6 were stored in a shed at Cranberry, listed as Not Needed. Number 4 was taken out of service on July 4, 1928, and was retired on May 31, 1936. Number 6 stayed in service much longer but was taken out of service on October 9, 1932. The locomotive was officially retired on May 5, 1937, with the boiler being sold to a knitting mill in Kingsport, Tennessee, in July. So, by the end of 1937, all three of the Consolidations were gone, part of a clean-up program initiated by new master mechanic, Clarence Hobbs.

These three Consolidations represent the second era of ET&WNC and Linville River history. They ran through the same beautiful scenery, mastered the same grades, and handled just as many trains as the later Ten Wheelers. The old timers, the ones who worked for the railroads for decades, fondly remembered them as the “little engines.” These were the locomotives they learned their trade on, and every engineer remembers the locomotive he qualified on to mark up as an engineer instead of a fireman. They should be remembered by all ET&WNC fans as the locomotives that made the railroad prosperous, and able to afford the later, larger locomotives that made this little narrow gauge system famous.

Those wanting to model these Consolidations have options. In O scale, one would have to convert an Overland Models C-18. Western Rails Company has designed 3D printed parts to convert an HOn3 Blackstone C-19 into #4 or #6. These parts include wood or steel cabs, extended smoke boxes with two styles of headlights, a new smokestack, flared tender shells, new domes, and an air reservoir under the cab. The smoke box can even be ordered with the number on the plate. Check them out at https://westernrails.com/. RailMaster Exports sells an ET&WNC version of their Sn3 Consolidation kit.